Why are the same words spelled differently in American and British English?

Why are the same words spelled differently in American and British English?

British and American English have plenty of differences.

Many of them are circumstantial. The words "trainers" and "sneakers", for example, simply developed separately in each country after their invention.

But those famous spelling differences were no such accident of history.

The spelling of English was inconsistent for centuries.

Not only did spelling change from generation to generation, but in any given era there was plenty of variation. Within reason, people basically spelled words however they liked.

There had been several English dictionaries, but they were failry insufficient.

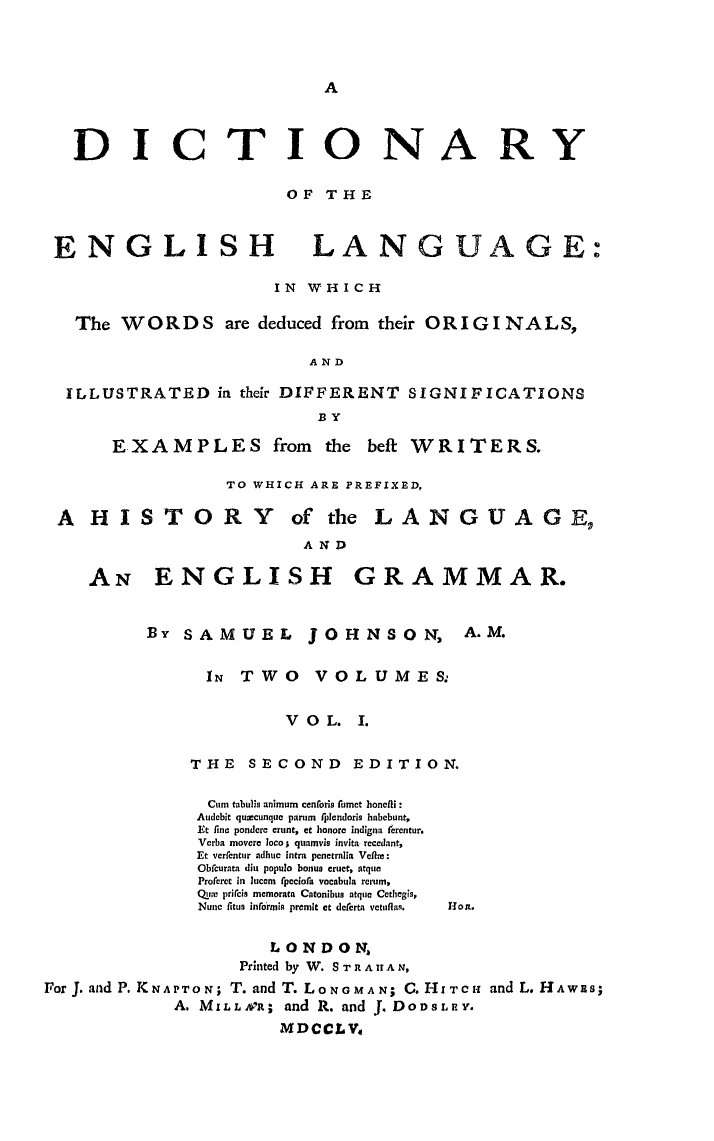

So the great scholar Samuel Johnson was contracted to create a definitive version. After a monstrous nine years of solitary work Johnson's Dictionary was published in 1755.

Johnson had to make decisions about spelling, but his interest was primarily in collating known words.

He had established something like the first official orthography - spelling system - in English, but his spellings lacked any regularity or real rules.

Johnson's Dictionary became the definitive English dictionary, both in form and content - it set the standard for all else that would follow.

And though many of his suggested spellings would evolve over time, Johnson's overall lack of consistency survived in British orthography.

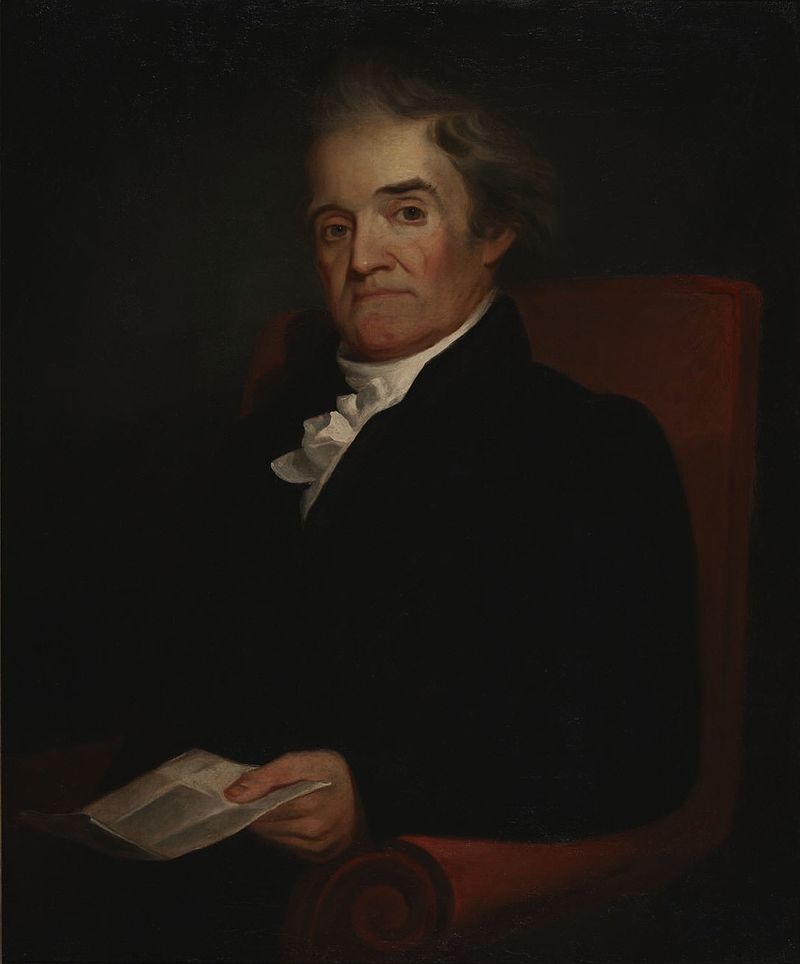

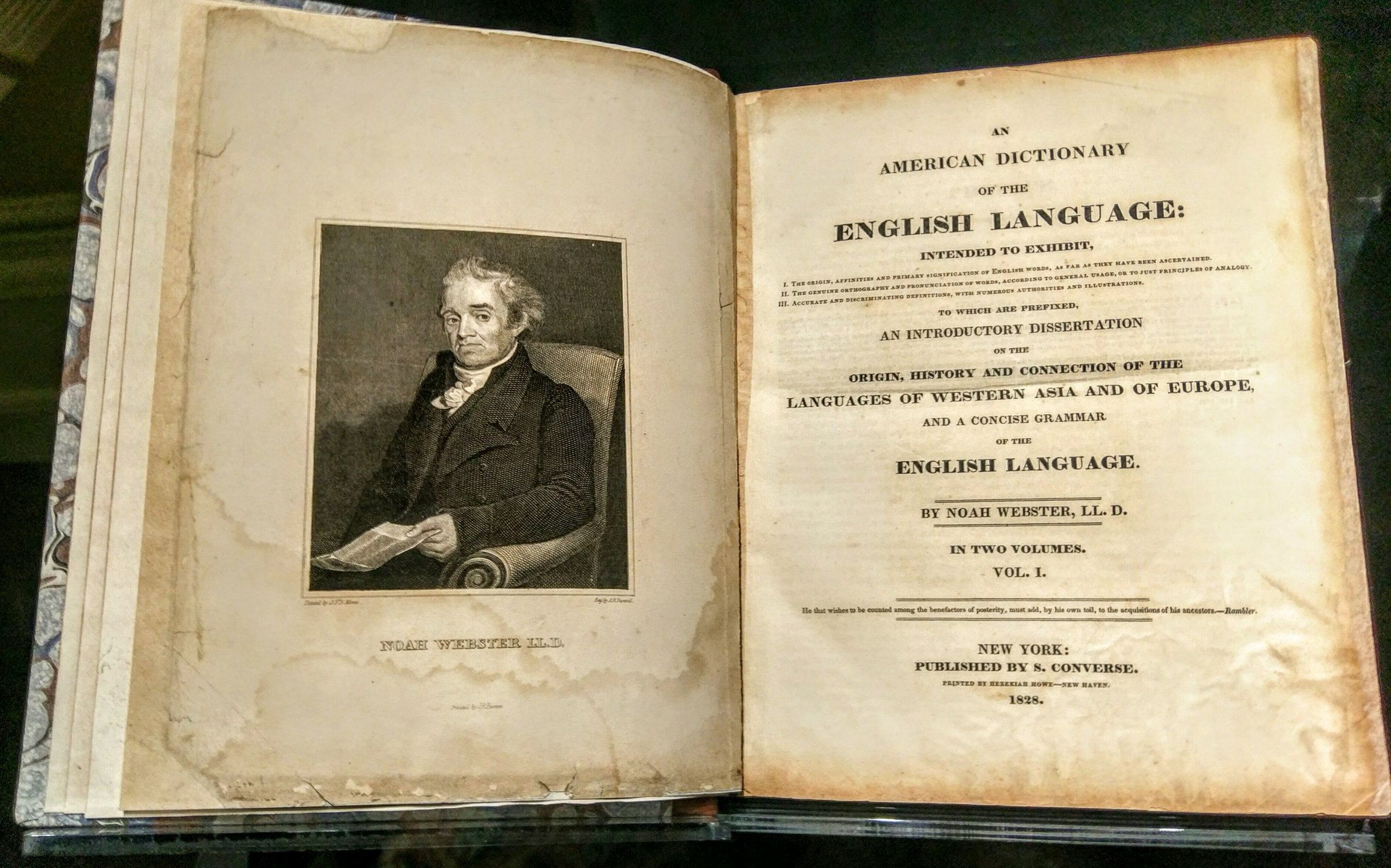

But, in the early 1800s, an American scholar called Noah Webster decided to create an English dictionary for his own country.

He was a patriot and he was passionate about education. And so, dissatisfied with Johnson's dictionary, he wanted to improve it.

Webster's intentions were dual.

On one hand he thought a dictionary with standardised and coherent spelling would be better for education and literacy.

And, politically, he saw the opportunity to create a distinctive American orthography, to achieve linguistic independence.

In 1806 he published the Compendious Dictionary of the English Language, in which many of his rules were established. And in 1828 he published the American Dictionary of the English Language, complete with 70,000 words.

This was the product of two decades' work.

There were many changes Webster made to Johnson's original spellings, including the replacement of -our with -or, of -ise/-yse with ize/yze, of -re with -er, or of -ce to -se, and of -ll with -l in derivatives of nouns ending with one l.

These, and many more.

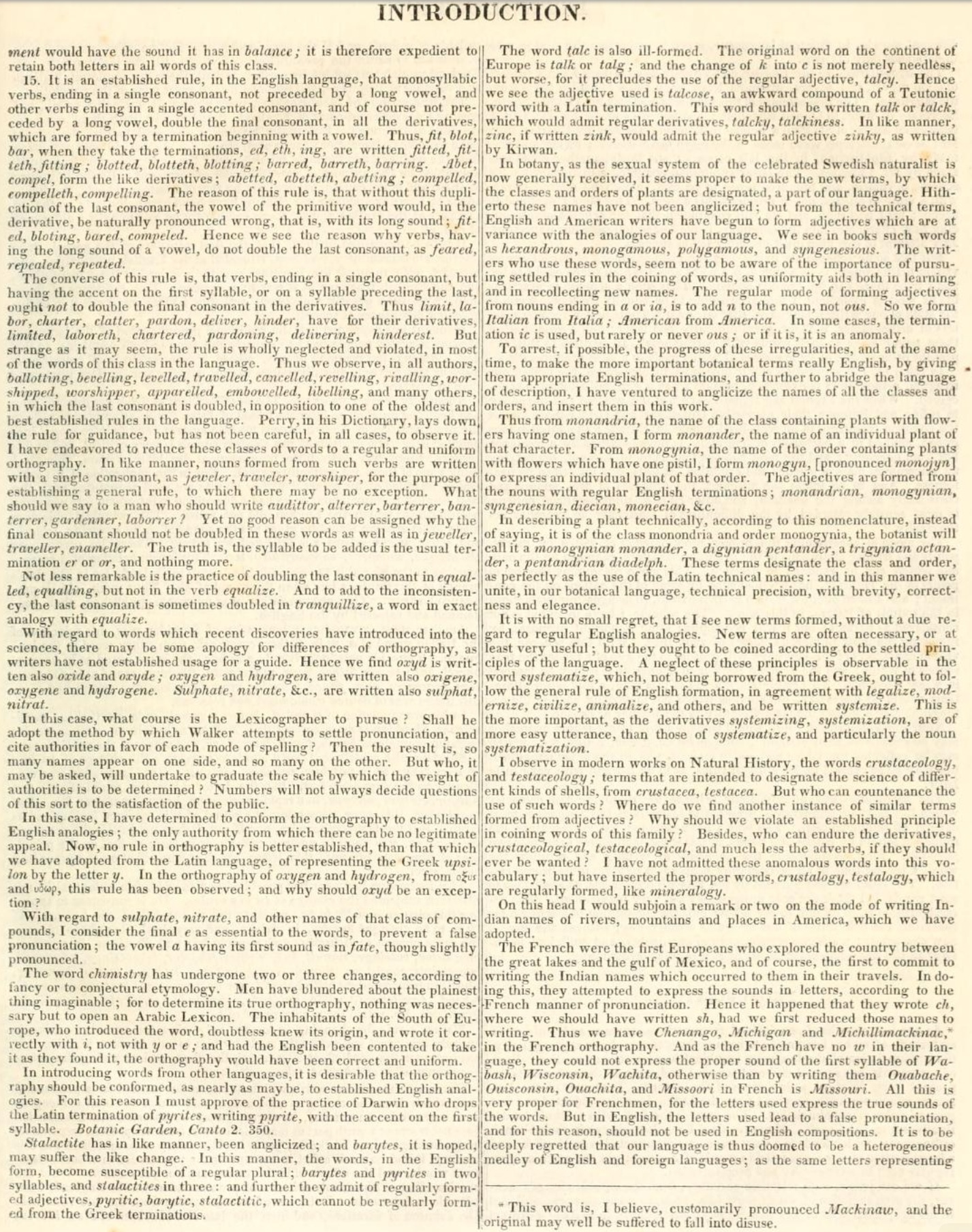

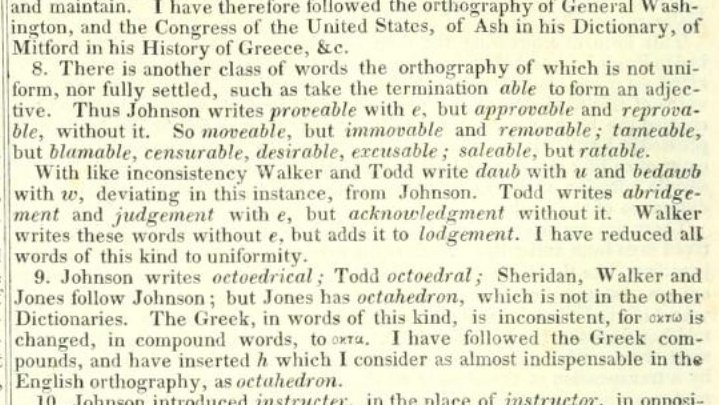

In his introduction to the 1828 dictionary, Webster explains his reasoning for any and all changes he made to Samuel Johnson's original spellings.

Throughout he shows himself to be extremely learned in both linguistics and etymology. He had a good reason for everything he did.

Webster's primary concerns were simplification, consistency, pronunciation (that words should be said how they are spelled), and etymology (that words should conform to their origins).

#8 shows Webster's frustration with inconstistency, and #9 his etymological care.

But Webster didn't invent these alternate spellings.

Many of them were already popular in America and had long existed in Britain too. Rather, it was Webster who collated and formalised them into a consistent orthography, who chose which spellings would be definitive.

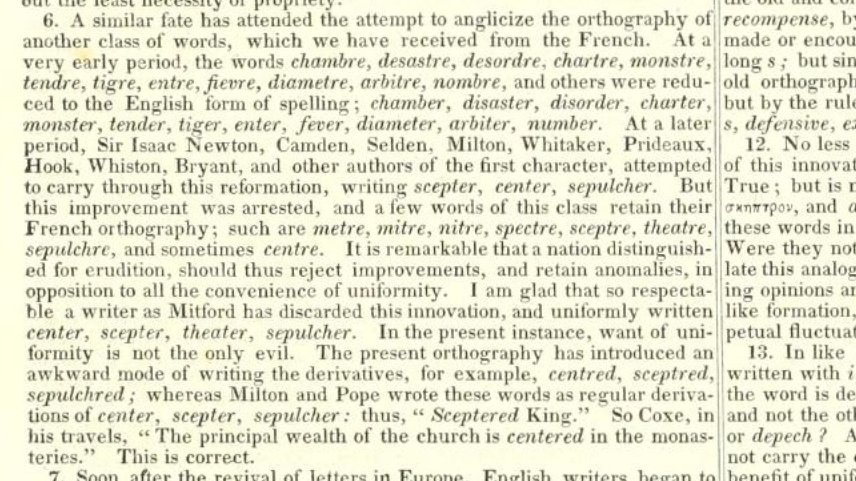

Here Webster discusses the difference between -re and -re words like centre and center.

He certainly pulls no punches in his analysis, and is forthright about what he considers to be "correct".

The common theme throughout his work is a desire for regularity and rationality.

Webster was clearly unimpressed with the frivolities of British writers, and though an admirer of Johnson was quite ready to point out his mistakes:

Noah Webster's dream was to create a rational, consistent, useful, unifying, independent, and deeply American orthography.

And his suggestions have now become the standard; his dream was realised, and Britain and the USA shall forever spell the same words differently.

Indeed, his principles outlived him - and not only in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, a direct descendent of his original.

For example, when planes were invented, the USA ended up with "airplane" and the British with "aeroplane" (from French), following Webster's orthography.

And so, unlike the circumstantial differences between American and British English, those of spelling are highly intentional - they are American by design.

As Oscar Wilde wrote in 1887: "we have everything in common with America nowadays except, of course, language."