Why did artists in the past paint the same thing over and over again?

Why did artists in the past paint the same thing over and over again?

The Madonna and Child - Mary holding the infant Jesus - was one of the most commonly depicted scenes in Western art for centuries.

From the gold-laden portrayals of the International Gothic style:

Given the vast number of paintings of the Madonna and Child, many are given names based on their unique features or qualities.

Such as Pisanello's Madonna of the Quail from 1420, so called because of the quail depicted alongside Mary and Jesus.

Mary holding the infant Jesus was also a popular image in the icons of the Eastern Orthodox Church, where it is known as the Eleusa.

Why are there so many different versions of the Madonna and Child by so many different artists?

Well, they're all forms of Marian art. Marian refers to Mary, who has been the object of her own special worship and veneration for centuries.

But that in itself doesn't fully explain why she and the infant Jesus were painted so many times.

The practical reason is that there was popular demand for them - a force which has always shaped and guided art.

For example, many of these depictions of the Madonna and Child were for personal use.

Filippo Lippi painted this one for Giovanni de’ Medici in the 1460s.

This Madonna and Child, painted by Peter Paul Rubens in 1621, was commissioned to be part of the funerary monument of Anne Antheunis and her recently deceased husband - featuring portraits of them both offering thanks to Mary.

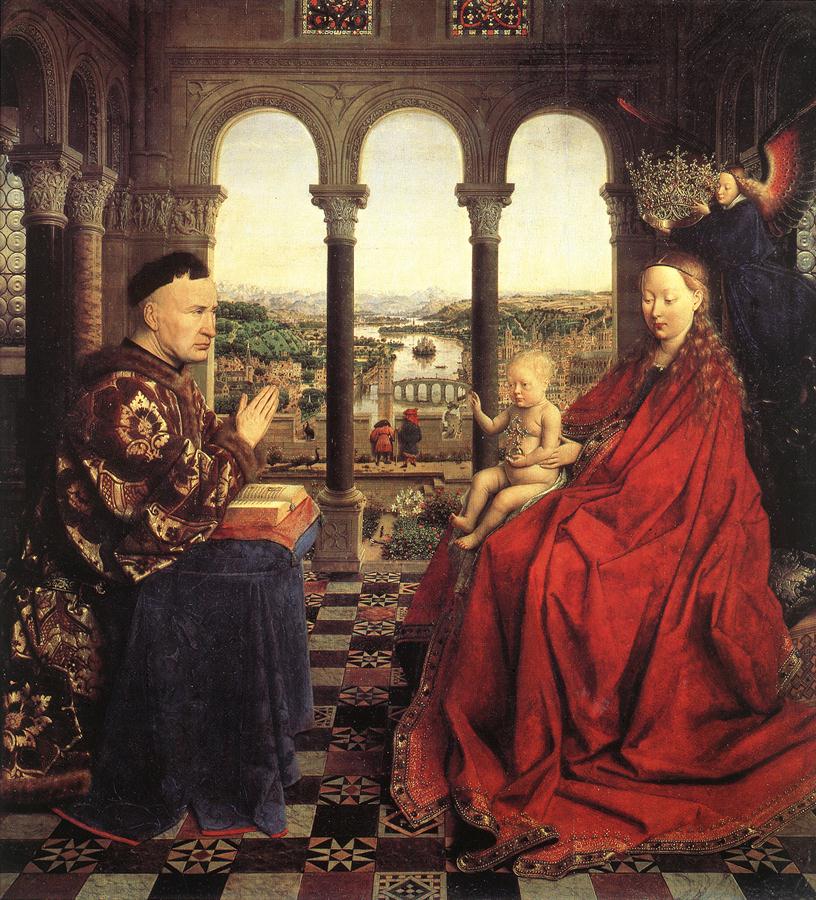

These "donor" portraits, where the individual who funded the artist's work was placed in the painting alongside Mary, were not uncommon.

It was a way of securing one's legacy and an act of religious devotion.

As in Jan van Eyck's Madonna - next to the donor, Chancellor Rolin.

Most of these paintings of the Madonna and Child were altarpieces.

Whether for new churches or old ones, there was constant demand for such religious art.

As when Perugino's Madonna and Child was painted for the recently restored Convent of San Domenico in 1493:

After his victory in the Battle of Fornovo in 1495 Francesco Gonzaga, Marquess of Mantua, built the Church of Victory and commissioned Andrea Mantegna to paint a Madonna and Child for its interior - including Francesco himself in adoration in the lower left.

The colossal Maestà of Duccio, created for Siena Cathedral in 1311, was paraded around the city before its installation.

That should tell us something about the role such art played at the time of its creation.

Because, seen in such context, these paintings seem rather different.

Whether for private or public use, in houses or in churches, these paintings were objects of worship.

Still art, but not just art.

Of course, most of these paintings have left their original homes and are now in galleries or museums.

Such as Cimabue's Maestà, featuring the Madonna and Child, which was painted for Florence's Santa Trinita Church in 1290 but is now in the Uffizi Gallery:

The two panels of the rather striking Melun Diptych by Jean Fouquet (1452) have been separated and are now in different countries - one in Germany and the other in Belgium.

Great art exceeds any context, but seeing it without that context obscures the fact that art was rarely made for it's own sake.

Galleries and online images can make us forget the intimate relationship between art and the socio-cultural conditions of the society that produced it.

We might even think that some of them are beautiful paintings, but as shown by what an observer wrote about the parade of Duccio's Maestà in 1311, these depictions of the Madonna and Child were more than just paintings:

And so they supplied a constant demand and fulfilled a central social and religious role, like much art around the world and throughout history.

It can seem strange to talk of art as having function or purpose, but these many depictions of the Madonna and Child had exactly that.