Is cinema the greatest modern art form?

Artists aren't less talented than they were in the past, it's just that they're making films instead of paintings...

Is cinema the greatest modern art form?

Artists aren't less talented than they were in the past, it's just that they're making films instead of paintings...

Modern art might charitably be described as controversial - for a huge number of reasons.

But much modern art was never supposed to be "liked"; it has always been about provoking, challenging, and questioning.

Perhaps why it can so often seem like a bad joke.

Which might lead some to despair that art isn't what it used to be.

But maybe we're looking in the wrong place. Painting is only one form of art, after all, and there are many others which continue to flourish, achieving both popular appeal and artistic greatness...

And, that being the case, cinema has an awful lot in common with painting, especially on a technical level.

Take lighting, which has always been of supreme importance in art. Few mastered the use of light like Caravaggio with his distinctive, intense chiaroscuro.

And this is also true of cinema, where lighting is a vital tool in the evocation of mood and atmosphere.

Hence why there are professionals dedicated to lighting on film sets.

Colour, too, is a central element in any painting. Whether in the more subtle tones of Titian and Vermeer or the vivid yellows of van Gogh and the sumptuous blues of Monet.

And in films colour is just as significant - that's why colour grading and colour correction are such a big part of post-production.

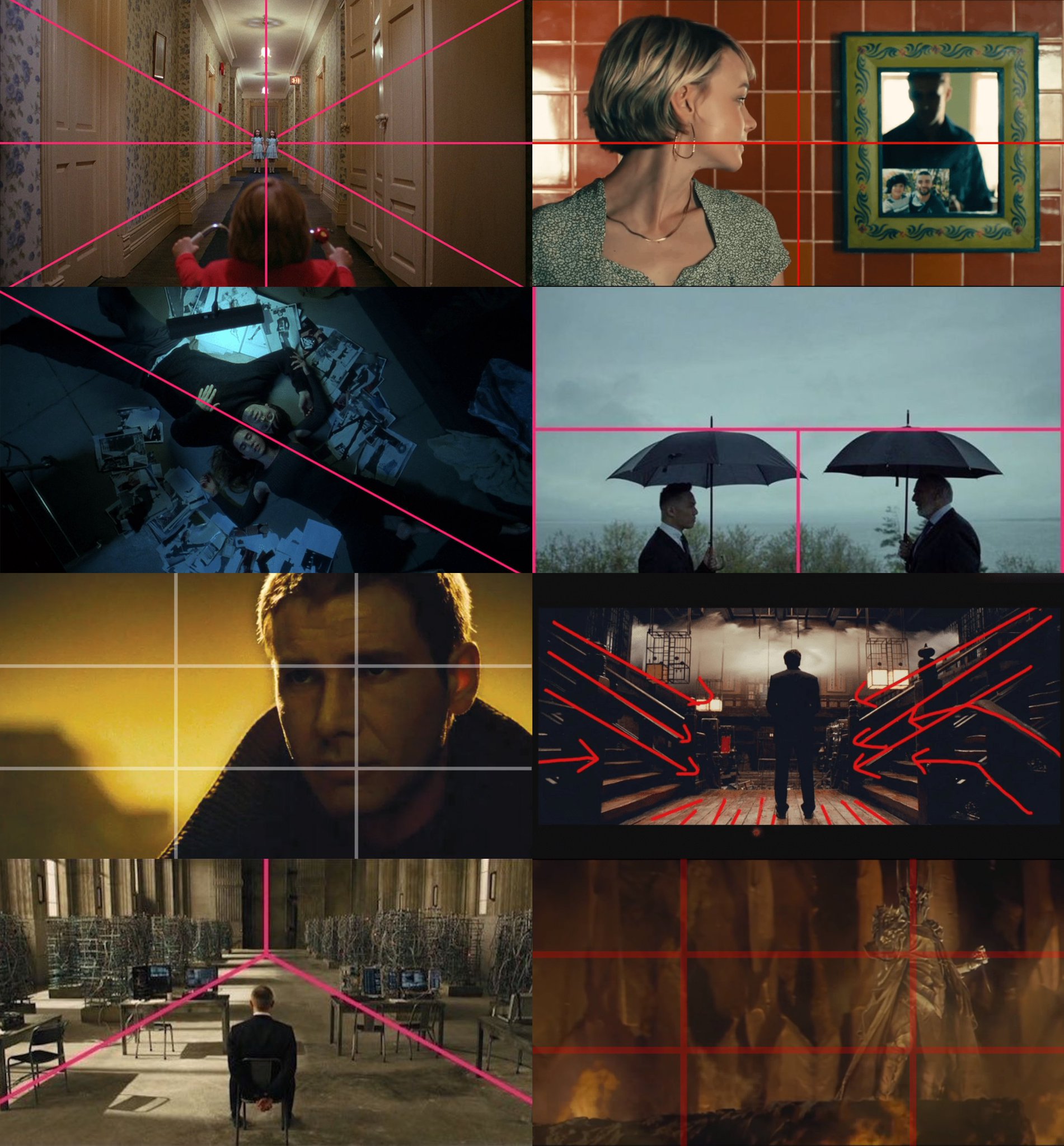

Composition has long been considered one of art's defining elements - the arrangment of figures and objects within a scene.

Hence Raphael's preparatory sketches for his Madonna of the Meadow, each with slightly different compositions - searching for the perfect arrangement.

And in cinema composition is no less important. It's what creates moments of such enduring power and memorability.

Many shots are painstakingly planned out and composed to achieve the maximum effect, to transmit the scene's meaning with subtle visual language.

The placement of figures (and their poses) and the environment around them is vital in guiding our eyes around the scene.

Certain balances are simply more visually pleasing - hence the frequency of similar compositional rules across art, cinema, and photography.

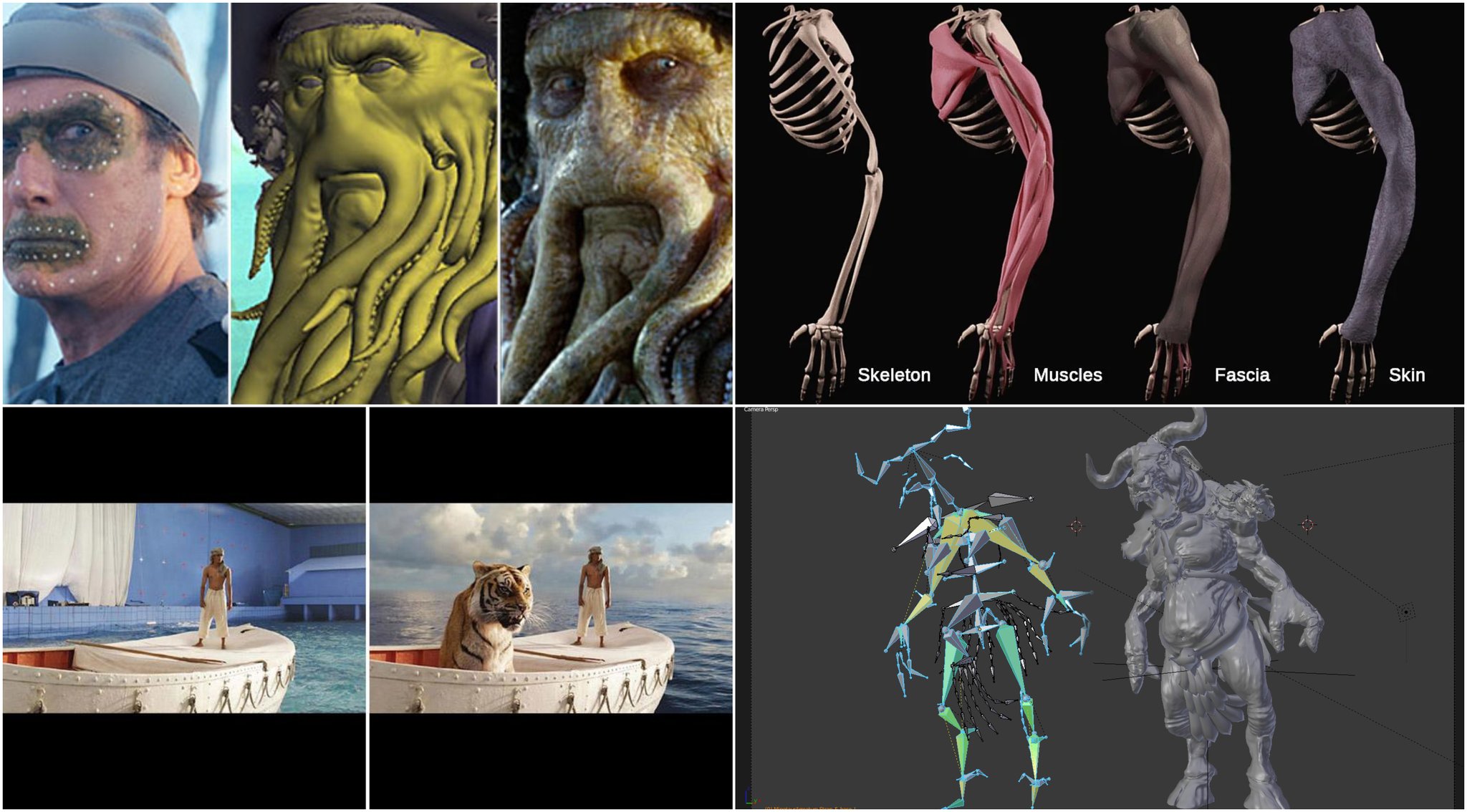

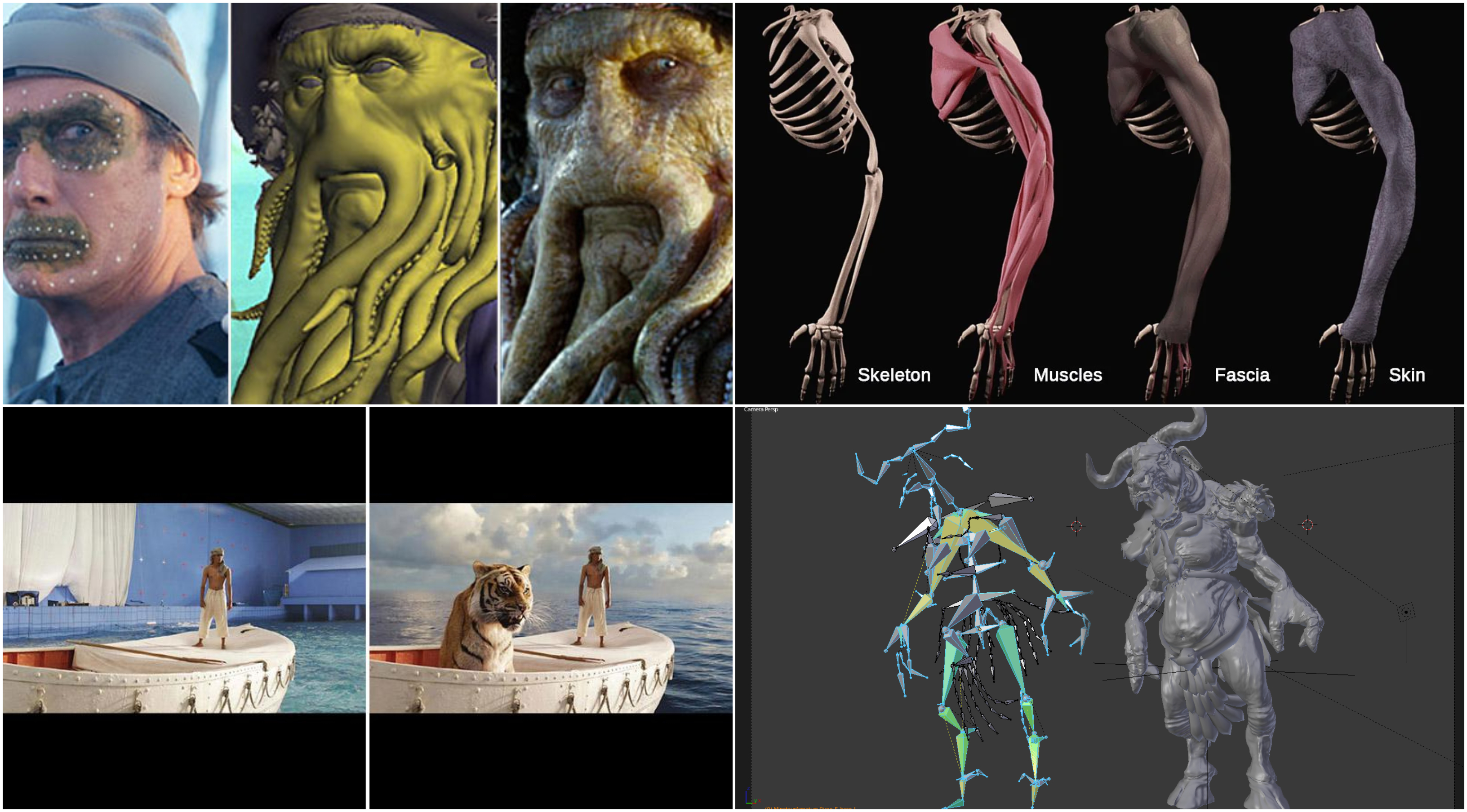

We should also remember that Renaissance painters were mathematicians, architects, engineers and scholars at the forefront of science and technology.

Leonardo researched human anatomy and argued that any artist must understand it in order to paint truly realistic human forms.

These painters made rapid developments in representing reality - using linear perspective, shading, real anatomy - and wrote treatises on optics, geometry, and composition.

Turning art from its flat, two-dimensional Medieval form into an illusion of the real world.

What is CGI if not an illusion of reality?

And, like those Renaissance painters, CGI artists are technological pioneers. Their ability to create realistic worlds relies on many of the same skills - digital, this time - even the rigging of animation models with virtual skeletons.

And CGI is but one part of the entire world of Special Effects, which ranges from real-life explosions to minutely detailed models and everything in between.

Peter Jackson's famous use of forced perspective to make Frodo appear small in comparison to Gandalf is an old technique.

It was used by Borromini in the 17th century to make this statue appear lifesize despite being only 60cm tall, and the gallery far longer than it really is.

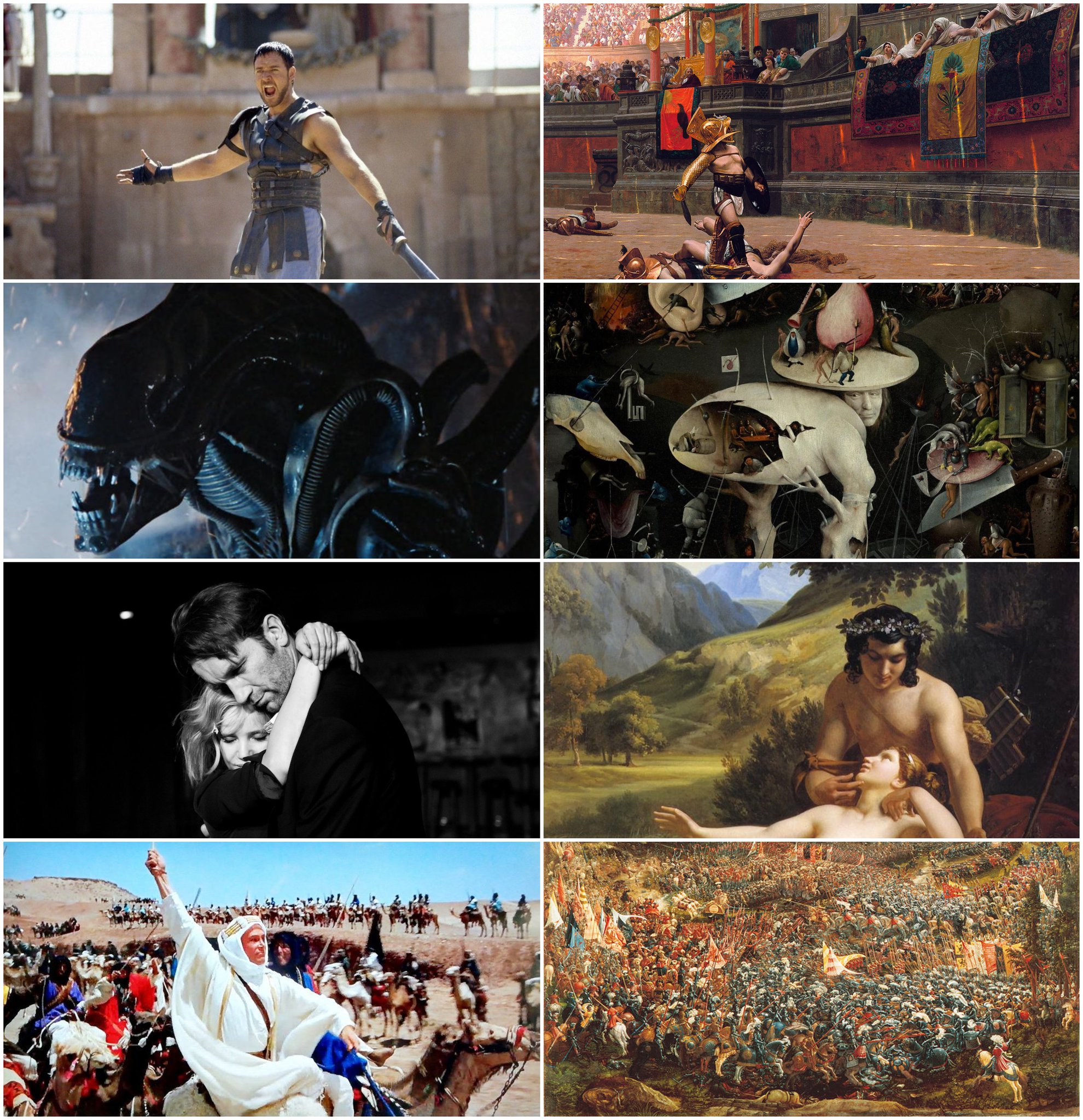

And cinema, just like painting, tells stories - some of them new and many of them familiar.

Historical epics, tales from mythology, romances and dramas, the fantastical and the mundane, the bizarre and the comedic and the terrifying.

They fulfil the same storytelling role.

There's even something to be said for the way artists once depicted mythological heroes time and time again, given their fame and the demand for such art, and how the same heroes and characters are portrayed so frequently on the silver screen.

And the use of music in cinema must be mentioned too.

Its soundtracks, drawing on a vast array of influences and often classical in nature, represent some of the greatest and most popular of all modern music.

If Mozart had been alive today, he'd have written film scores.

Howard Shore's score for The Lord of the Rings, for example, is an epic of musical storytelling for the ages, not so different from Wagner's Ring Cycle.

Ennio Morricone, John Williams, Hans Zimmer, and so many others are rightly considered composers of the highest order.

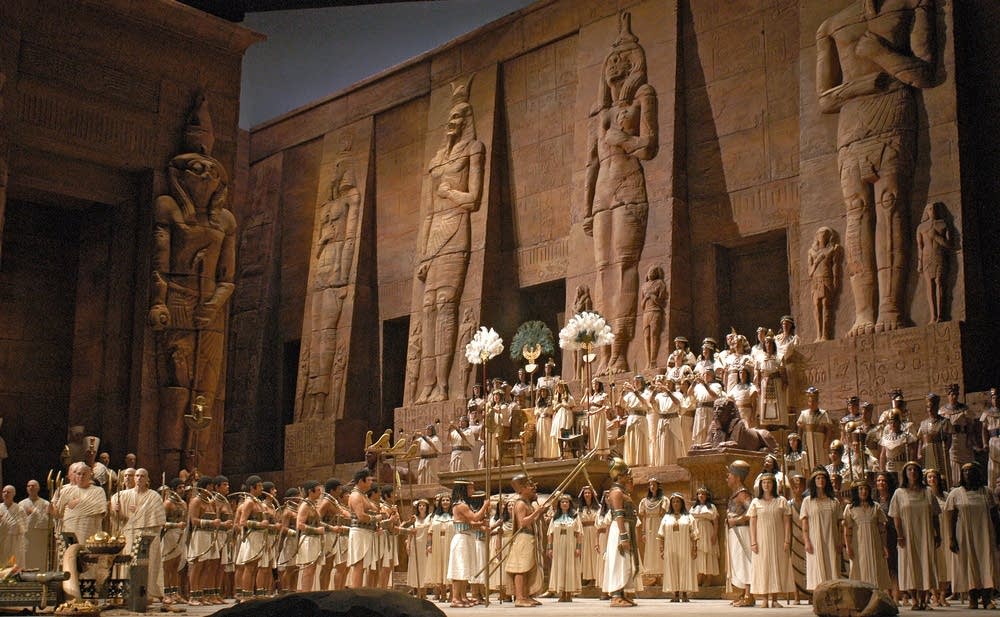

Indeed, film has much in common with opera - it unifies music, theatre, set design, costume, and drama into a single work of art.

Opera was popular entertainment in the 19th century and cinema is now; that doesn't prevent them from being - sometimes - truly great works of art.

Beyond all of these technical and thematic similarities what unites cinema and painting - perhaps all art - is their joint ability to evoke and inspire, to reflect and uplift, to move and rouse.

And, at their best, they can both be sublime.

People are no less talented now than they were five centuries ago - it's just that they might not be doing quite the same things they once were.

And so cinema - rather than painting or sculpture - may well be the definitive art form of the 20th and 21st centuries.