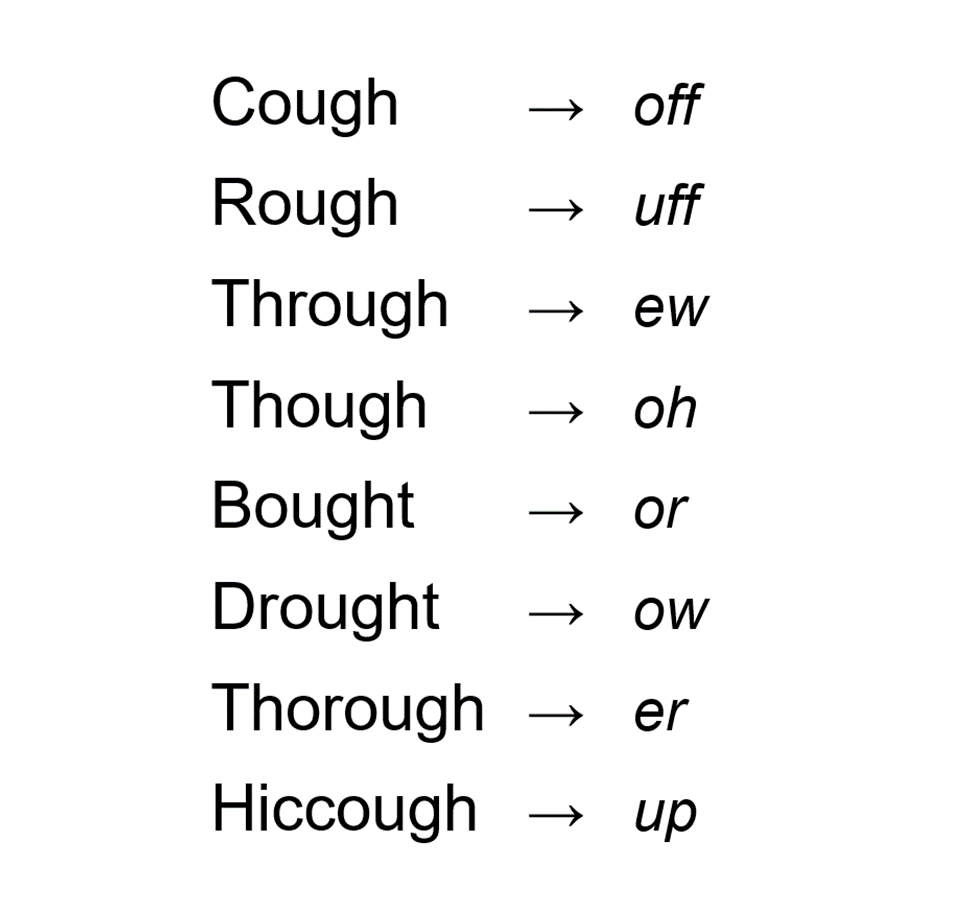

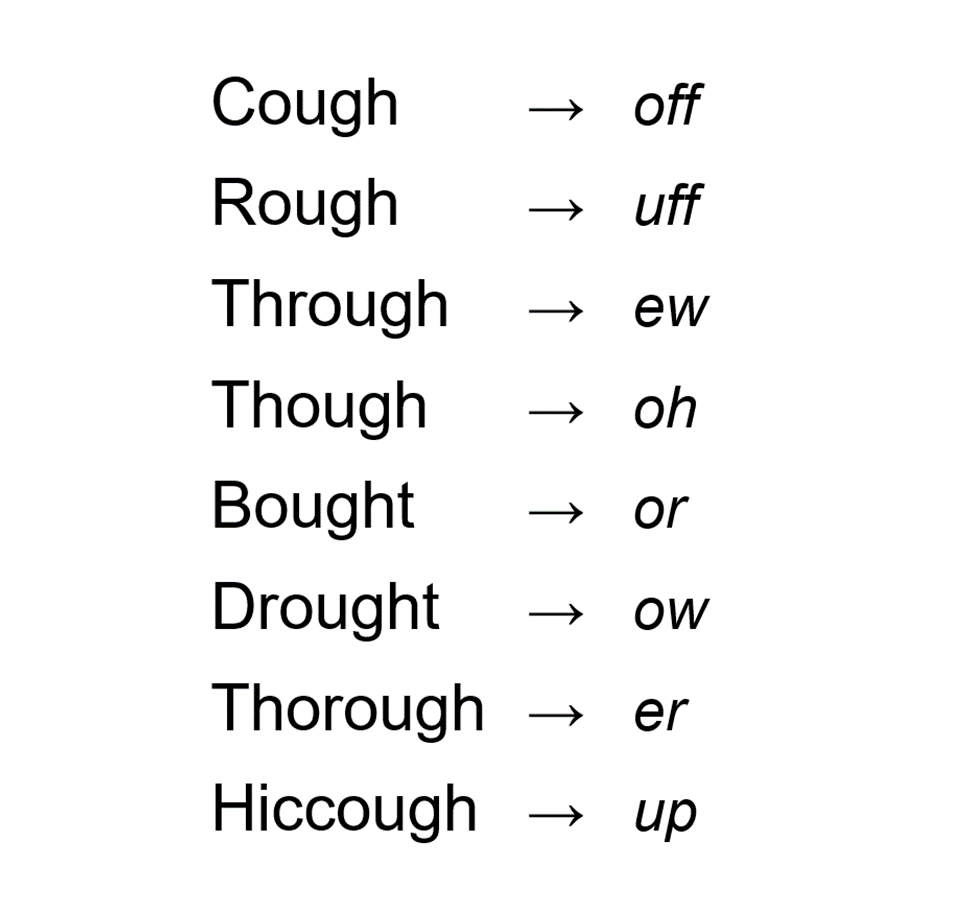

The letters "ough" can be pronounced at least 8 different ways in English.

How did that happen?!

The letters "ough" can be pronounced at least 8 different ways in English.

How did that happen?!

English has notoriously strange spelling.

The letters "ea" are pronounced differently in the words bread, break, earth, heart, meat, tear, and... tear.

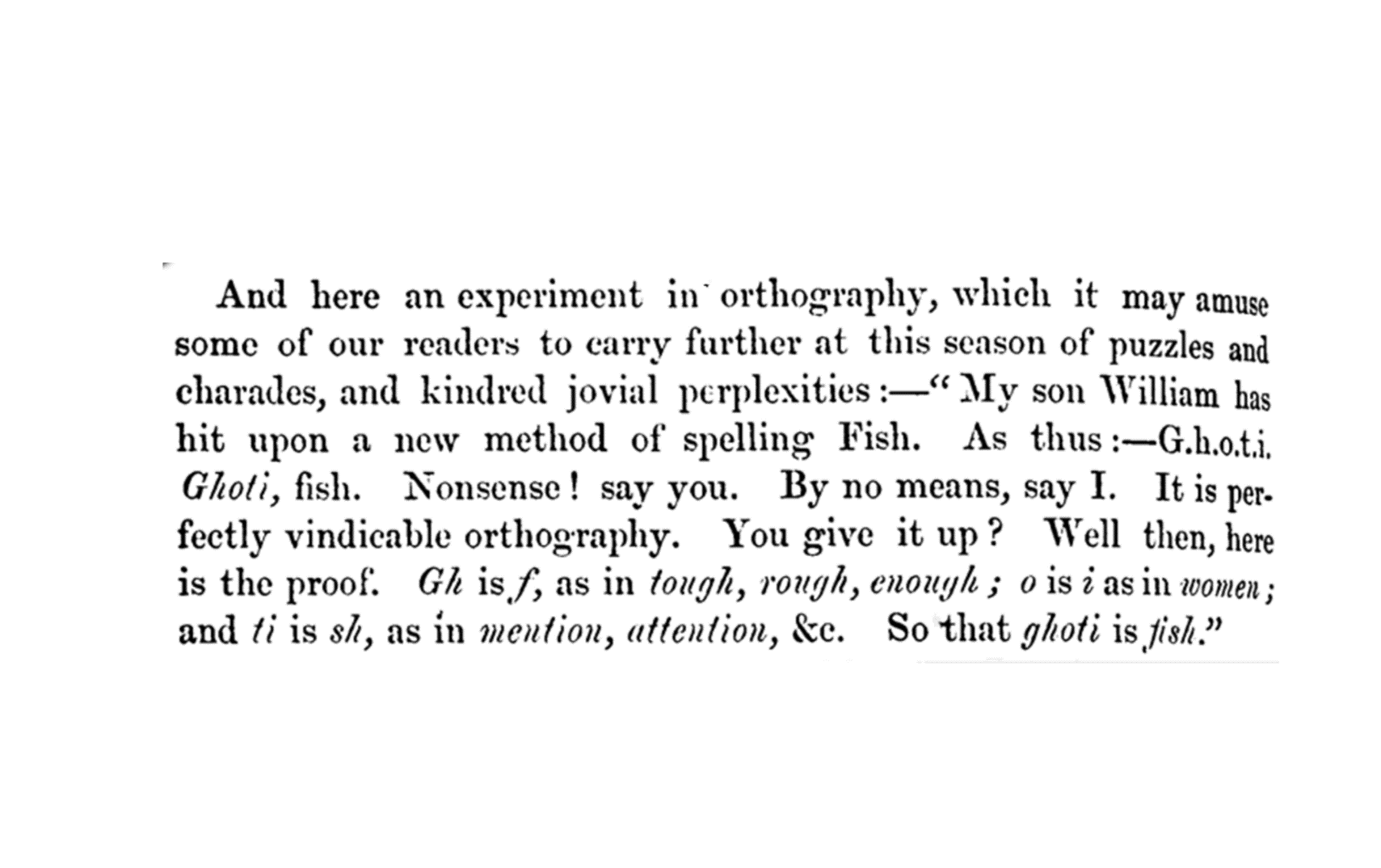

Horse and worse don't rhyme, but base and bass do, while the word "ghoti" could, technically, be pronounced fish:

It isn't unusual for certain combinations of letters to be pronounced differently, but in most languages there are rules and clear contexts for this.

Such languages, where its written form directly corresponds to pronunciation, are known as "phonemic".

In a phonemic language you can hear a word and know how it is spelled, or you can read a word and know how to say it.

But in English this is often not the case; the combination "ough" is particularly bad, as noted by Punch magazine in 1875:

The disalignment between spelling and pronunciation in English has several causes.

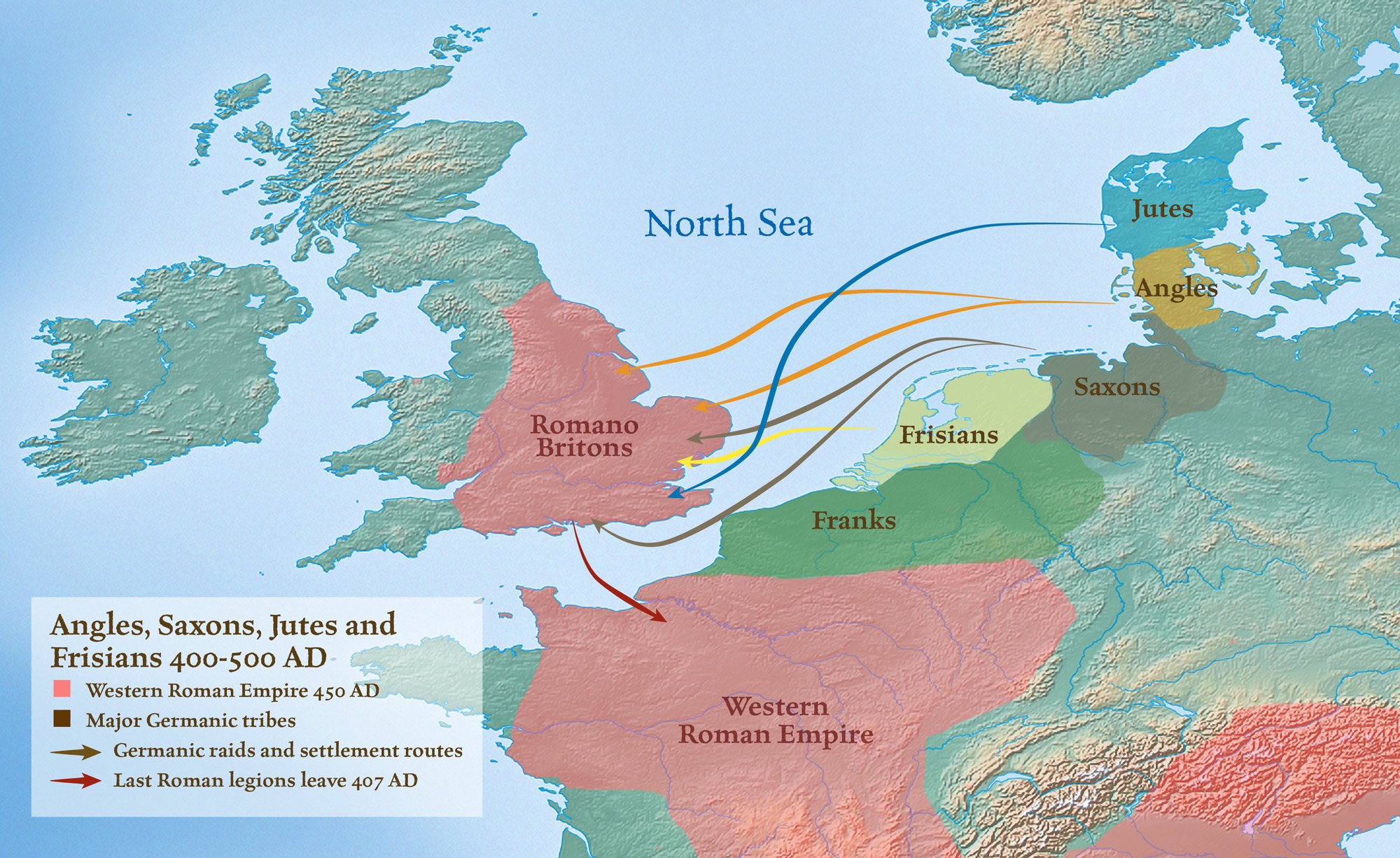

One of them is to do with how English developed as a language. Its origins lie in Old English, a Germanic language brought to Britain by the Anglo-Saxons in the 5th century.

After that came the Vikings in the 8th century with Old Norse, another Germanic language, and then in 1066 William the Conqueror and his fellows Normans arrived with French, a Romance language.

These three languages would meld together and create the English of today.

The full story is, of course, more complicated and long-winded than that.

French dominated as the language of the ruling class and the administration for centuries, while Middle English - a mix of Old English and Old Norse - was the language of everybody else.

And this explains several things, not least why English words relating to government have French origins - court, judge, jury, parliament.

And why there are synonyms in English which come from different languages, such as freedom (Old English) and liberty (Old French).

English eventually made a comeback. Henry IV, who ruled between 1399 and 1413, was the first King of England whose mother tongue was English and not French.

And this language had incorporated the words, spellings, and grammar of three linguistic traditions.

Still, this doesn't explain everything; many languages have similarly complex histories.

More important was Gutenberg's invention of the moveable-type printing press in 1440, brought to England by William Caxton in the 1470s.

This was one of the most important technologies ever invented because it allowed the creation and circulation of written works on a scale previously impossible.

It also meant the printers had to choose particular spellings for the words of the texts they were printing...

And so many words had their spellings codified in the 15th and 16th centuries.

This Middle English orthography forms the basis, with a great many twists and turns, of modern English spelling.

But Middle English was more or less phonemic, so what happened?

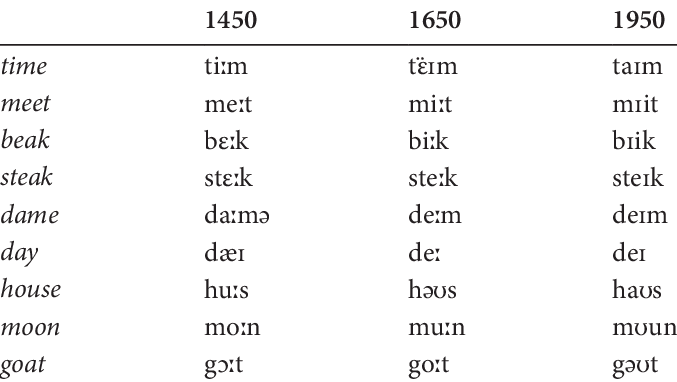

The "Great Vowel Shift" is what happened, which had already started in the 1400s but only ended in about 1700.

It was a process whereby Middle English vowels lost their old Germanic pronunciations and became the ones we use today.

"Out" used to be pronounced "oot", for example.

The point here is that those Middle English spellings, which were once phonemic, remained the same, while their spoken pronunciation changed.

Thus creating a disparity between the way words are written and how they are pronounced - one that has endured to the present day.

Still, there was no uniform spelling system and spelling has evolved too - but rarely for reasons of pronunciation.

William Shakespeare spelled the same words differently, such as "allye" and "allie" for the modern alley, and he spelled his own name at least six different ways.

In the 17th and 18th centuries many words were imported into English from Latin and Ancient Greek, bringing across their spelling even when it didn't accord with English rules.

And some English words were given a more Latin spelling, as when receyt became receipt, from receptum.

When Samuel Johnson made his dictionary in 1755, the first truly comprehensive dictionary of the English language, he didn't standardise spelling so much as codify it and make decisions based on his own tastes.

As Noah Webster, the American spelling reformer, pointed out:

Noah Webster in America would try and standardise British English into a more rational American variant: hence his replacement of "our" with "or" and "ise" with "ize" and so on and so forth.

He was successful, but even American English remained far from phonemic.

And so here's the other crucial part - there has been very little top-down reform in English, which is unusual.

Most languages around the world have been standardised and, importantly, these processes have either been relatively recent or are still ongoing.

Most notorious is the Académie Française, founded in 1635, which has for nearly four centuries carefully managed the French language.

For example, as part of a resistance to "unhelpful" Anglicisations, the Académie often creates new words instead of borrowing them from English.

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries language academies and institutions have worked to codify and unify the divergent linguistic traditions of their countries.

Nation-building played a big role in this, but so too did efficiency and an interest in improving literacy.

As recently as 1996 German-speaking countries agreed a collective linguistic reform, and such language updates are common around the world.

A consistent and simplified writing system, and one which is phonemic, is much easier to learn and understand.

And so the letters "ough" can be pronounced at least eight different ways because spoken English has changed while written English, despite evolving, hasn't changed to match it.

And because, unlike in other languages, this disparity has never been properly reformed.