Why are the Ancient Greeks so important? Why do people talk about them so much?

Well, it has something to do with Socrates, who was put on trial by his fellow citizens and sentenced to death.

The crime? Asking too many questions...

Why are the Ancient Greeks so important? Why do people talk about them so much?

Well, it has something to do with Socrates, who was put on trial by his fellow citizens and sentenced to death.

The crime? Asking too many questions...

It's important to ask why the Ancient Greeks are regarded so highly.

Is there actually a good reason for it?

We can talk about their maths or their architecture, their poetry or their politics, but in the end what matters most is their philosophy.

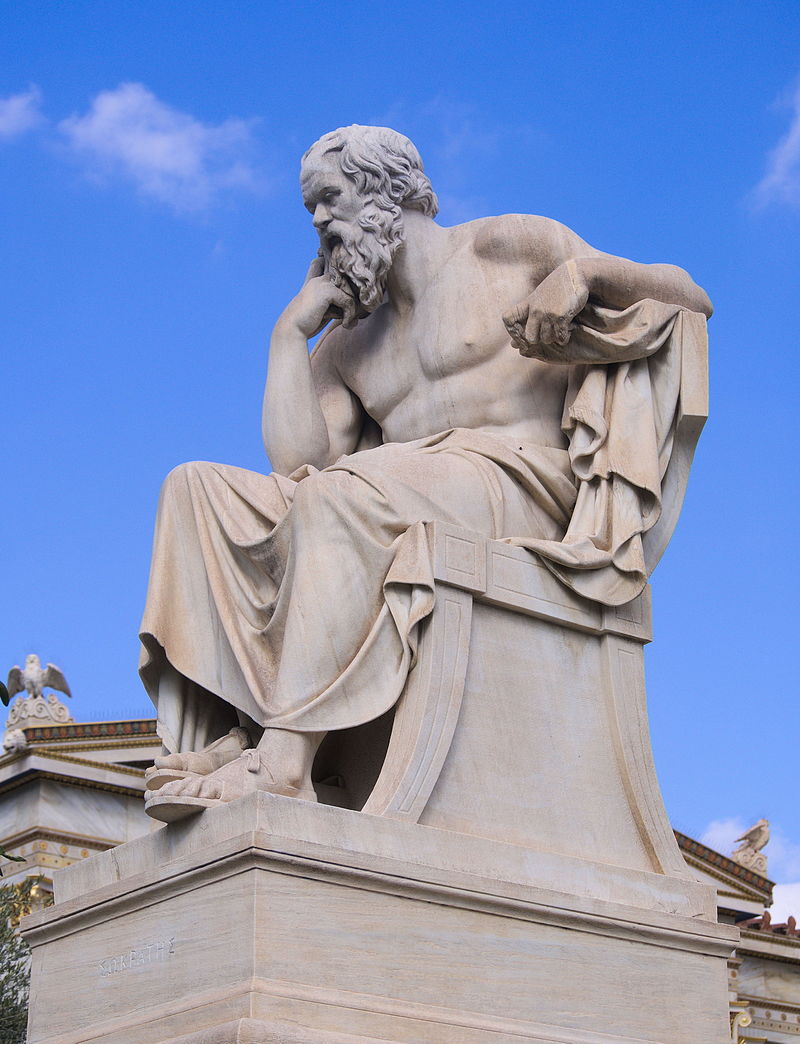

Although there were philosophers before him, Socrates marked a turning point - he embodies what Ancient Greek philosophy was all about.

He was born in 470 BC in Athens and lived during the city's Golden Age, when it flourished politically, culturally, and economically.

Socrates, who had fought in the Peloponnesian War, was uninterested in wealth or material comfort; he walked around barefoot and didn't care for his appearance.

What interested him was the pursuit of wisdom and virtue. His method of reaching them was to question everything.

And he never wrote anything down.

What we know about Socrates' ideas comes entirely from other people, especially his students.

Foremost among them was Plato, who subsequently influenced almost all of western philosophy.

But in 399 BC Socrates, aged seventy, was put on trial by his fellow Athenians. What were the charges?

Failing to acknowledge the gods of the city, introducing new gods, and corrupting the youth of Athens.

A jury of 501 attended the trial, including Plato, who wrote it down.

This was a turbulent time for Athens. They had lost the Peloponnesian War and their democracy had recently been overthrown in an oligarchic coup.

Democracy was back - but it felt fragile. And, to many, Socrates must have seemed like a threat to the city's stability.

When quizzed about his influence over the youth of Athens - several of whom had taken part in those anti-democratic coups - Socrates flatly denied having ever taught anybody anything.

Socrates only ever asked questions - he never claimed to be a teacher.

Indeed, Socrates explained during his trial that this was why so many people hated him and wanted him punished.

Because by his questioning he had exposed their own ignorance and aroused their hatred - the charges, he said, were a pretext.

He freely admitted that those who listened to him, especially the youth, had gone on to question their parents and the city's elders - a rift was appearing between the generations.

And yet, Socrates explains, there were no specific teachings of which he could be accused.

But the jury voted (by a margin of just thirty) that he was guilty on both charges.

After that he was sentenced to death; Socrates would have to drink a cup of poison hemlock.

But he refused to beg for mercy - that would have been demeaning, both for him and for Athens.

And Socrates, apparently, wanted this.

Another of his pupils, the warrior-historian Xenophon, believed that Socrates preferred death to exile in old age.

He wrote of how Socrates refused to ask for a lesser punishment and did not let his friends help him escape.

Xenophon's point was that Socrates saw in his potential death sentence the chance to die as he had lived, virtuous until the end.

"The difficulty, my friends, is not to avoid death, but to avoid unrighteousness."

And this is what Jacques-Louis David depicted in his 1787 painting.

While Socrates' friends and followers despair, he remains calm, taking his chance to offer one last moment of wisdom.

That life was not about avoiding death, but about living the right way.

Xenophon recounts how he remained cheerful and rational throughout the trial and right up until his death, comforting and even chiding his friends.

And how, in the end, he drank the cup of poison like it was wine.

This was probably the most important thing Socrates said during his trial, as recounted by Plato:

"The unexamined life is not worth living."

He believed the mind is humanity's greatest gift, and that to use it in the pursuit of wisdom and truth is the greatest good.

Plato's account of the trial is not all one-sided.

Socrates evidently conceptualised the gods very differently to most Athenians - he even claimed to have been divinely inspired and given a special quest to provoke, question, and rouse his fellow citizens.

So we can understand why the Athenians punished Socrates. His unorthodox ideas were destabilising in a city whose democracy was fragile.

But they made him a martyr; Socrates has become the symbol of rationality and intellectual enquiry, and of the modern, scientific world-view.

"The unexamined life is not worth living."

That, in a single line, summarises the essence of the legacy of Ancient Greece - not a specific set of beliefs or ideas, but a way of thinking.

A way of thinking that has shaped the world as we know it today.

I've written about this before in my free, weekly newsletter.

Every Friday, along with historical figures like Socrates, I also write about art, architecture, literature, and music.

To join 70k+ other readers, consider subscribing here: culturaltutor.com/areopagus