Where did your daily cappuccino come from?

Well, it involves the Ottoman siege of Vienna in 1683, a group of Italian monks, and a Polish spy.

But the story begins 700 years ago with a city in Yemen called Mocha...

Where did your daily cappuccino come from?

Well, it involves the Ottoman siege of Vienna in 1683, a group of Italian monks, and a Polish spy.

But the story begins 700 years ago with a city in Yemen called Mocha...

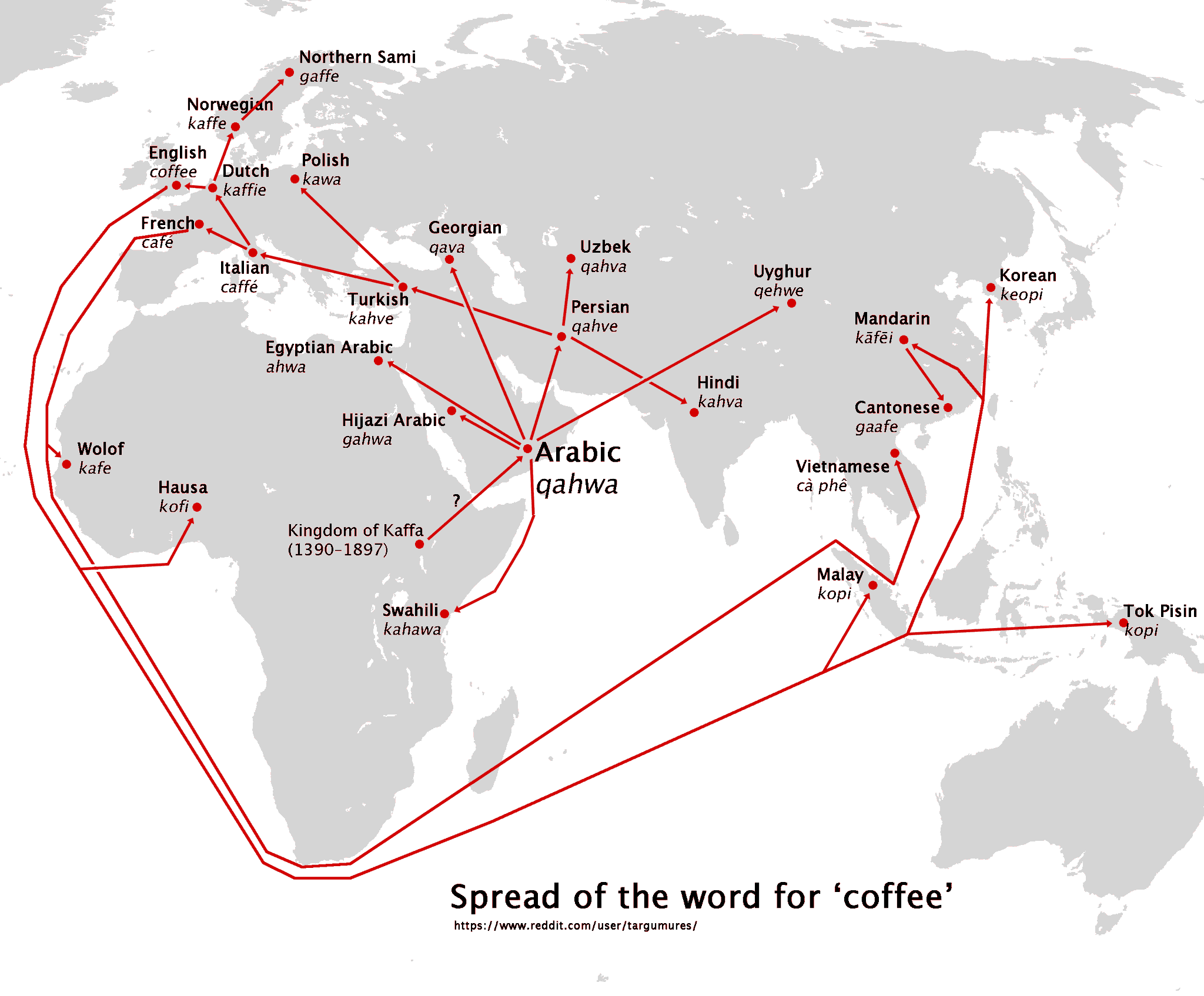

Where does coffee come from? The clue is in its name.

Coffee is an Anglicisation of the Dutch word koffie, which comes from the Italian caffè. That came from the Turkish kahve, which itself originates in the Arabic word qahwa.

Coffee originally came from Ethiopia, where various legends involving mystics and shepherds explain how people first came to drink it.

By the 14th century it had reached Yemen, and from there it spread all around the Middle East.

The city of Mocha in Yemen was the heart of the coffee trade for centuries, exporting beans to the Ottoman Empire and all over Europe.

It's from this city that the Caffè Mocha got its name, along with Alfonso Bialetti's world-famous Moka Pot.

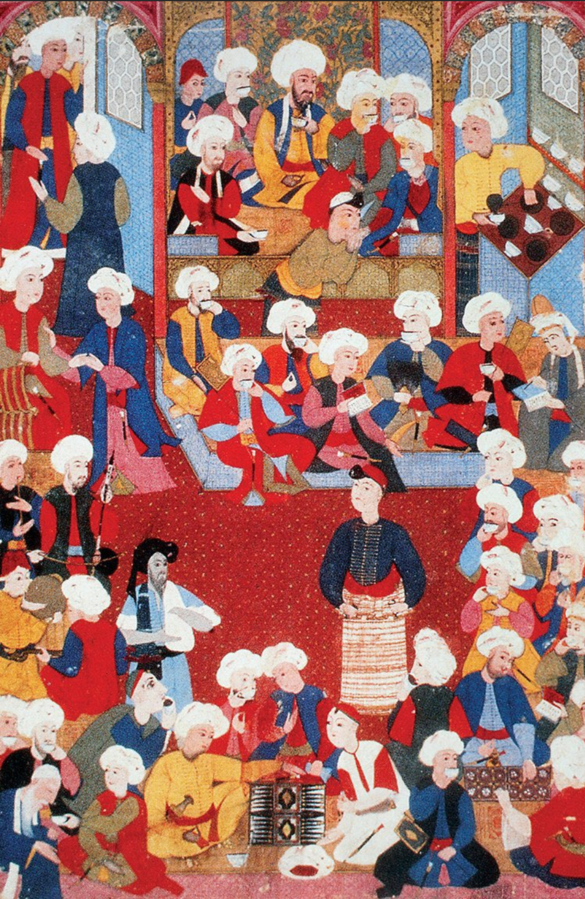

The Ottoman Empire was where coffee culture as we know it today first appeared.

Popular history says that in 1475 a coffeehouse called Kiva Han was opened in Istanbul, soon to be followed by thousands more across the vast Ottoman Empire.

Turkish coffee is prepared by boiling water with finely ground beans in a cezve - it's been drunk that way for centuries.

But coffeehouses weren't just about the drink itself; they have always been places of socialising, conversation, gossip, politics, and entertainment.

It was via trade with the Ottomans that coffee entered Europe, first into the great Italian port cities of Venice, Naples and Trieste - hence why so many coffee-related words have Italian roots.

As for France, coffee first arrived there with the Ottoman ambassador in 1669.

Coffee had a mixed reputation. Doctors admired its medicinal properties - helping digestion - and scholars found it useful for staying awake while working.

But it met with religious resistance, being condemned as the "devil's drink", until Pope Clement VIII gave his approval.

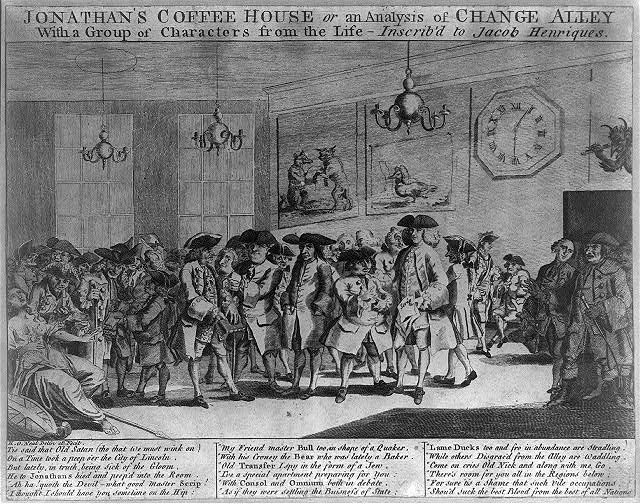

The first coffeehouse in Europe was founded in the 1640s in Venice and over the next decades they appeared all over Europe, often set up by entrepreneurial immigrants or merchants.

They were modelled on their Ottoman equivalents and fulfilled the same socialising function.

A crucial moment came in 1683, with the failed Ottoman Siege of Vienna.

The retreating Turkish army left behind sacks of coffee beans which ended up in the hands of a Polish diplomat and spy called Jerzy Franciszek Kulczycki.

With them he opened the first coffeehouse in Vienna.

Kulczycki also made the revolutionary decision to add milk.

And people noticed that when a few drops of milk were added to coffee it took on the brown colour of the robes worn by Capuchin monks, known as Kapuziner in German.

That's where the modern cappuccino gets its name.

During the 18th century the number of coffeehouses skyrocketed all around Europe; they offered a vital gathering place that was neither work, church, home, nor centred around alcohol.

They were a place where ideas were born, and their influence on the Enlightenment was immense.

In 1735 the composer JS Bach even wrote a piece of music called the Coffee Cantata. It included these lines:

Oh! How sweet coffee does taste, Better than a thousand kisses, Coffee, coffee, I've got to have it, And if someone wants to perk me up, Oh, just give me a cup of coffee!

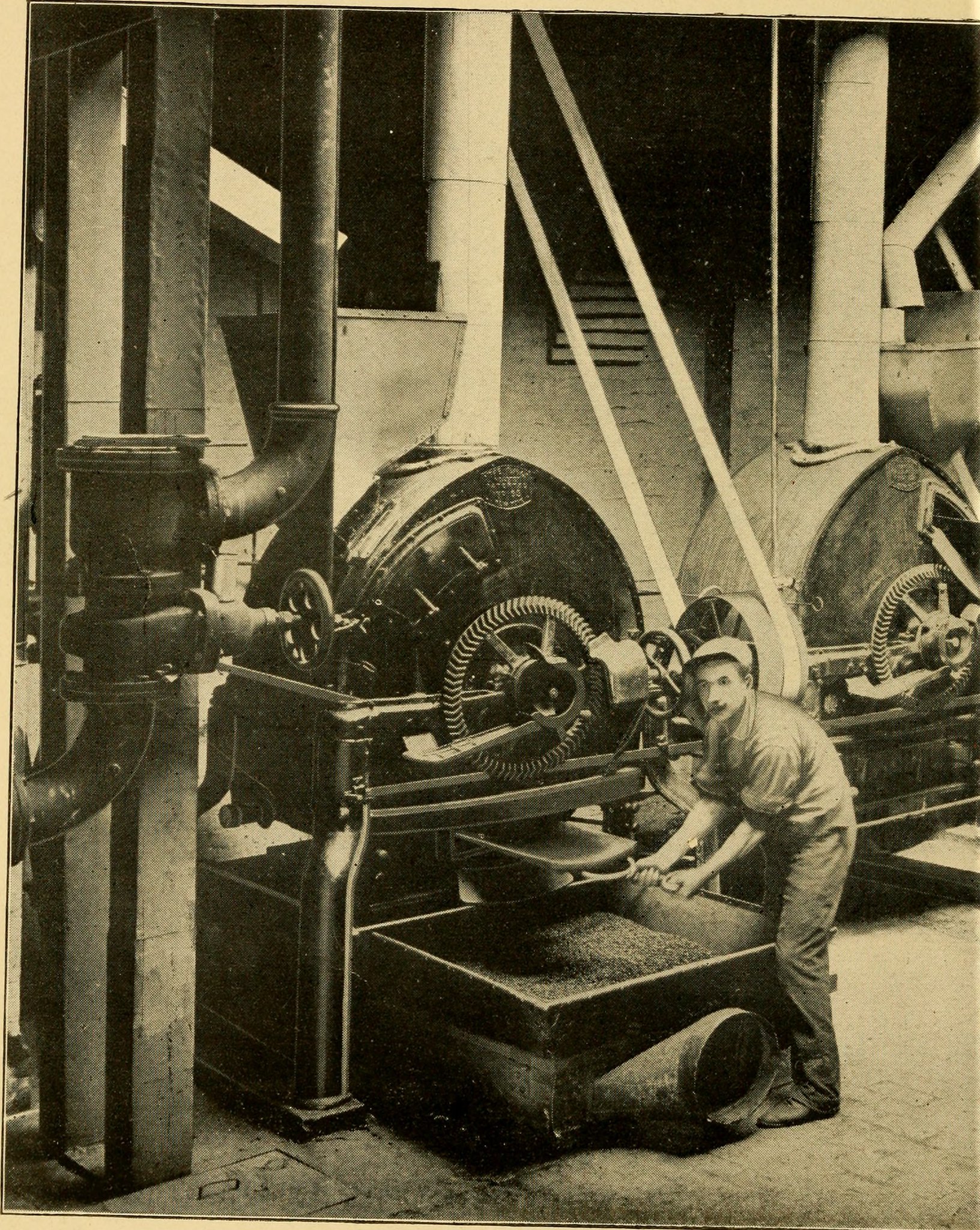

During the 19th century, in large part thanks to the Industrial Revolution, coffee was well on the way to becoming a global industry in the modern sense, with new technology allowing for its production on a vast scale.

Coffee advertising went through the roof, too.

But such demand far outstripped what could be supplied from Ethiopia via Yemen; since the 1600s European powers had operated coffee plantations in their colonies, usually worked by slaves.

And by 1852 Brazil (then independent) became the world's largest exporter of coffee.

In England coffeehouses had been replaced by teahouses, but in Europe they were booming.

These thousands of cafés were important for everyone from radical political groups to regular folk who wanted a coffee before or after work - not so different to how it is now.

And it was in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that coffeehouses got their reputation as hubs for writers and artists, whether in Paris or Vienna or Buenos Aires.

Picasso, Hemingway, and Gauguin are just three of the famous guests who spent time at Le Dôme Café in Paris.

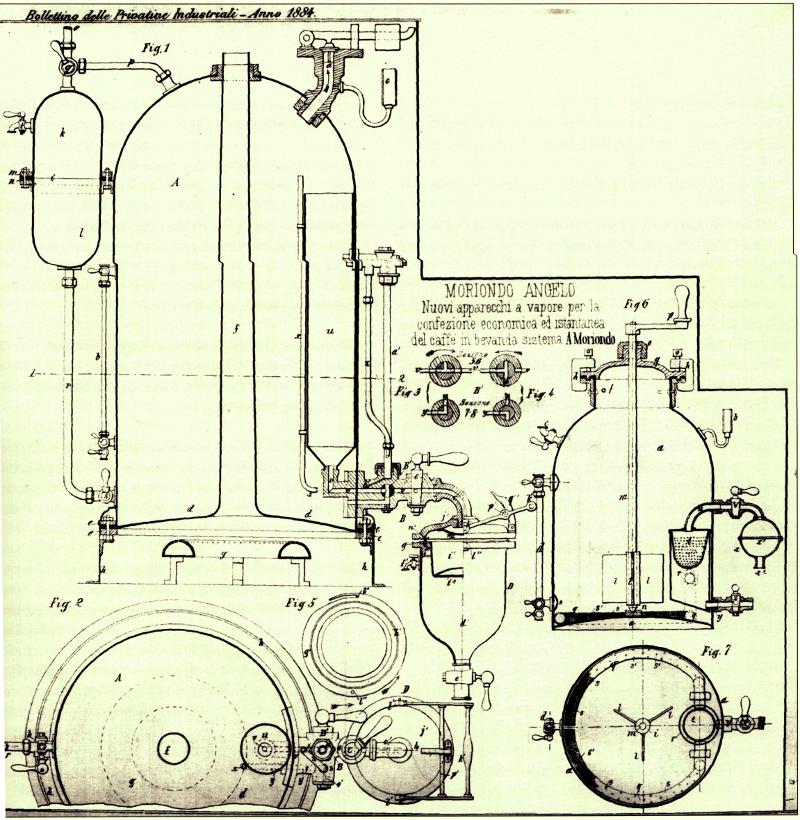

The earliest espresso machine was invented in 1884 by Angelo Moriondo and improved in 1901 by Luigi Bezzera, though it would take until the 1950s for espresso machines to become widespread.

They were a revolution, fundamentally changing the way coffee is made and consumed.

In the 21st century coffee is characterised by a mix of huge international companies and artisanal cafés.

But in many ways the coffeehouse has barely changed since its creation in the Ottoman Empire six centuries ago - they remain, as ever, a crucial part of everyday life.

If you enjoyed this then you might like my weekly newsletter.

It features seven short lessons every Friday - tomorrow's edition will include the music of Maurice Ravel, the explorer Zheng He, the Bell Rock Lighthouse, and more.

Consider subscribing here: culturaltutor.com/areopagus