In 1865 an American artist called Frederic Edwin Church painted the Northern Lights.

The thing is, he'd never actually seen them. But he was such a good artist that he didn't even need to...

In 1865 an American artist called Frederic Edwin Church painted the Northern Lights.

The thing is, he'd never actually seen them. But he was such a good artist that he didn't even need to...

Frederic Edwin Church was born in 1826 in Connecticut. He was from a wealthy family and that gave him the time and resources to pursue his greatest passion: painting.

And at the age of 18 he was introduced to an English-born painter called Thomas Cole...

Cole had emigrated to America in the 1810s and found in its beautiful mountains and vales a worthy subject for art.

He founded the Hudson River School, a group of landscape artists dedicated to painting the vast wilderness not only of the Hudson River Valley but all of America.

The Hudson River School was strongly influenced by European Romanticism, which emphasised the sublimity and beauty of nature.

We can see the Romantic influence on Church, who often depicted small human figures lost in vast, untamed landscapes - a typical feature of Romantic art.

Stylistically, the artists of the Hudson River School liked to carefully conceal visible brush strokes, thus producing a photoreal quality.

But these were not mere imitations of reality; in each painting they subtly rearranged the natural landscape to suit their artistic goals.

Church became Cole's star pupil, and in time he became perhaps the greatest artist of the Hudson River School.

That doesn't mean the others weren't also great. Albert Bierstadt's landscapes are radiant and gloriously precise visions of natural beauty.

While Sanford Gifford certainly had an eye for colour and the atmospheric effects of light, refracted through clouds and haze or reflected by water.

But there's something about the scale with which Church imbued his landscapes; they feel immense. And, even more than that, they are filled with drama and emotional weight.

He played with the "real" landscapes he observed to create a more heightened, visceral reality.

His later works have a lyrical, thoroughly poetic quality.

Whereas other members of the Hudson River School focussed almost purely on nature or embraced an Impressionistic interest in light, Church was always fascinated by the relationship between humans and nature.

There's often an ambiguity to his art; it has a rich and compelling symbolism.

This isn't just a portrayal of natural beauty. The sun looming through the clouds of a volcanic eruption, a light in a window, a desolate grave, a rainbow: each seems to conceal a deeper meaning.

But there's always a risk of over-intellectualising art.

Perhaps Church simply loved the American landscape. He painted it with great passion, close attention, and an eye for subtle storytelling.

Just consider these minute details and stories hidden within his landscapes:

He was a hugely popular artist whose paintings sold for large sums. Crowds queued up to see them when first exhibited, both high society and regular people.

Why? They're breathtaking, and always filled with stories to find and interpret - notice here the cross in the lower left.

And Americans were much closer to the countryside in the 19th century than they are now.

Church's landscapes were familiar to people, his depictions of the relationship between humankind and nature a joy and a struggle they knew well, its vast expanse a part of their lives.

And nor were his meanings always ambiguous; with Our Banner in the Sky he was ready to embrace wholesale symbolism.

It was painted in 1861 and brings out a theme latent in the rest of Church's work - a deep interest in America as a country.

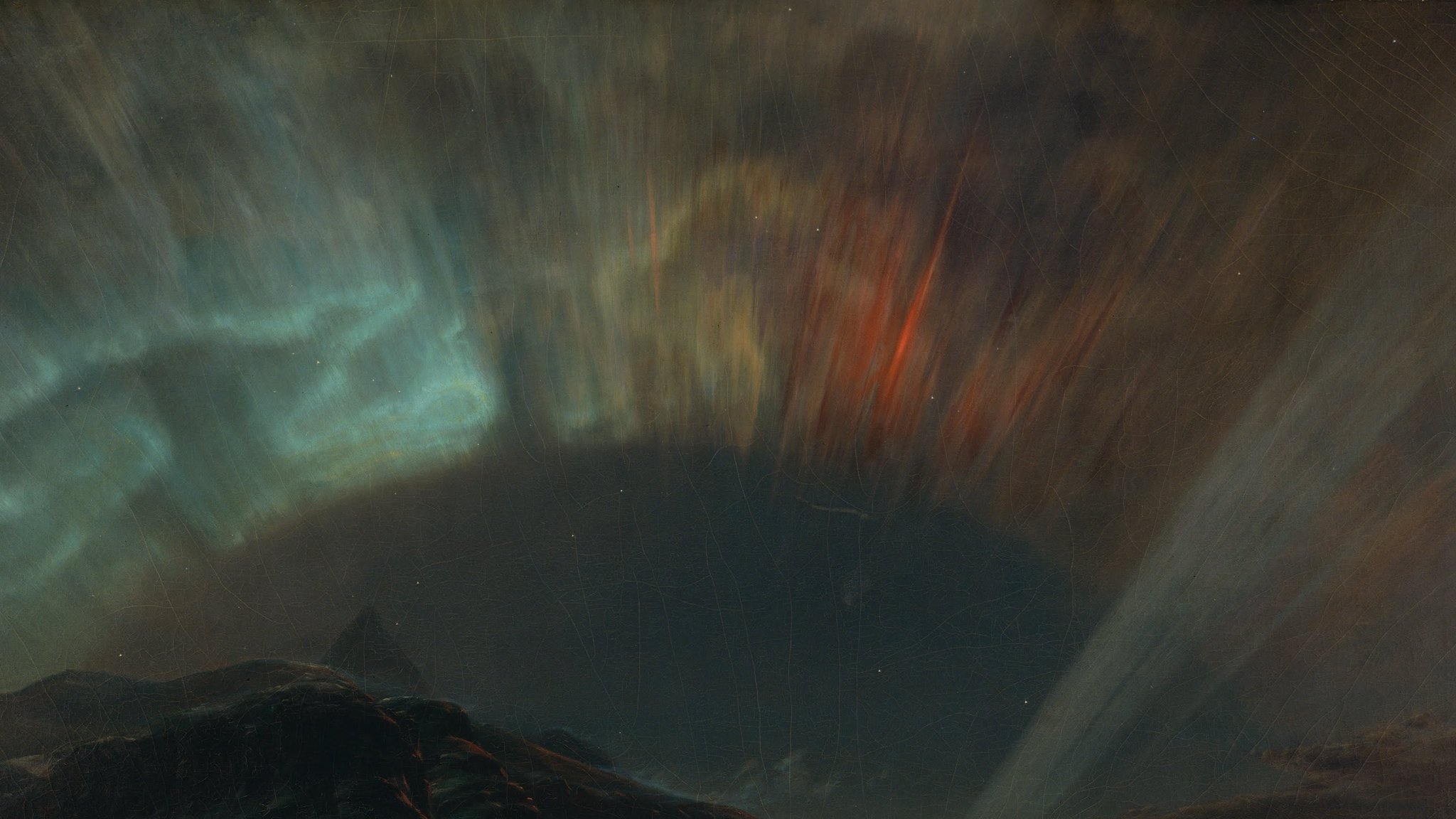

And it was in 1865, right at the end of the Civil War, that Church completed the Aurora Borealis.

It was inspired by the 1861 Arctic expedition of the explorer Isaac Hayes, a friend of Church. He provided sketches and a description of the Northern Lights.

The Northern Lights don't look much like Church's rendition of them, which was based on Hayes' account.

He portrayed them as a sort of celestial arc; photographs show us that it's more like a curtain. And green is their primary colour, but Church omits it almost entirely.

But even if it isn't "realistic", Church's vision does more than any photograph or photorealistic painting ever could to convey their beauty, mystery, and power, illuminating the dark and frozen Arctic night.

And that was Church's genius - to subtly reinterpret nature.

Here we see American Romanticism at its profoundest and most distinctive.

Casper David Friedrich, the great German painter, embodies a more pessimistic European Romanticism.

His version of arctic exploration has a ship destroyed by ice - nature victorious, humankind defeated.

In Church's Aurora Borealis things are different.

The ship is locked in ice - but it survives. And notice the small light in its cabin. A glimmer of hope. Then there's the explorer with dogsled, enduring the difficult night, surviving, looking for a way forwards.

It was a subdued form of optimism, but optimism nonetheless.

Church and the Hudson River School shared that Romantic love of the sublime and unconquerable beauty of the natural world - but they also seemed to believe that humanity had a place in it.

Which brings us back to its context. Was the Aurora Borealis related in any way to the Civil War?

Some have seen it as a symbol of hope in the wake of social strife and widespread suffering; uncertain, faltering, sombre, but profound and hopeful - a way forwards at last.

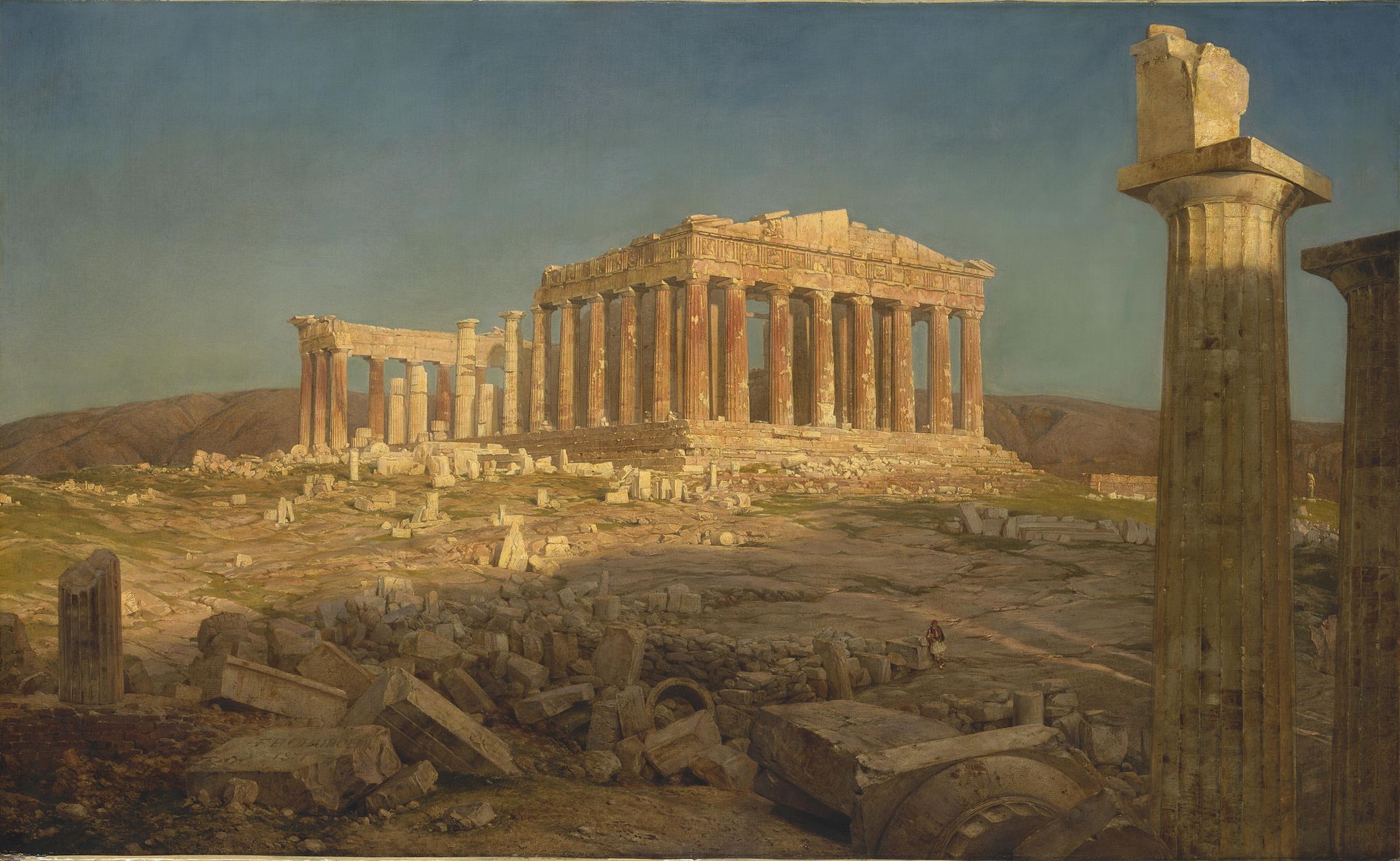

Church later travelled widely, first to Europe and then to the Middle East, where he painted everything from the Parthenon to Petra.

It's almost strange to see Old World scenes depicted by such a deeply American artist - we aren't used to seeing him paint places so ancient.

Church lovingly designed a house for himself and his family called Olana - it even had a view of the Hudson River Valley.

But from the 1870s onwards Church was beset by illness and painted little; he died in 1900, just one year after his wife.

The USA has produced many great painters, and Frederic Edwin Church deserves to be ranked among the finest of them.

Few artists of any era have captured the natural world in all its beauty and scale like Church, nor portrayed so poetically our place within it.