The popularity and worship of sports stars is nothing new - in the 21st century it's footballers and in Ancient Greece it was Olympic athletes.

But why are their statues so different?

Well, the Greek ones aren't actually statues of real people...

The popularity and worship of sports stars is nothing new - in the 21st century it's footballers and in Ancient Greece it was Olympic athletes.

But why are their statues so different?

Well, the Greek ones aren't actually statues of real people...

It's easy to imagine that the immense popularity of sport is an entirely modern phenomenon - it isn't.

Sport was just as important in Ancient Greece. For evidence we need look no further than the stadiums they built.

Then, like now, sport played an important role in society.

Football is the world's most popular sport now; then it was athletics.

Starting in the 8th century BC the Greeks held four great athletic contests: the Olympic Games, the Pythian Games, the Nemean Games, and the Isthmian Games.

Each took place in a different part of Greece.

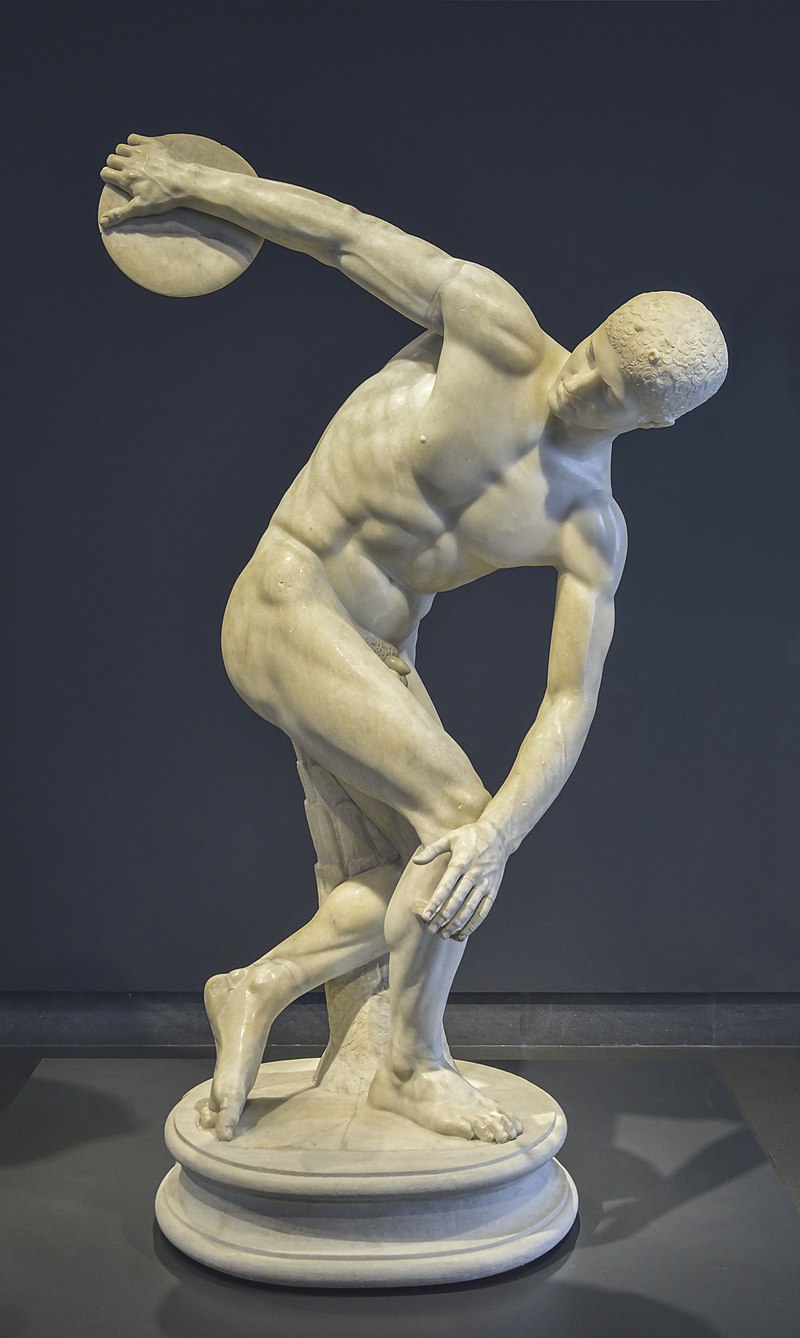

Events included boxing, wrestling, running, the pentathlon (which included javelin & discus) and archery - all components of the modern Olympic Games. There was also flute playing and, most prestigious of all, chariot racing.

Victors were famous throughout the land no less than political leaders, generals, or poets.

Poems called "epinikia" - victory odes - were written in their honour, praising their triumphs, weaving in stories of the gods, and spreading word of their everlasting glory.

And sculptures were made in their honour.

The famous Discus Thrower was created by Myron, an Athenian sculptor of the 5th century BC, though it - like most Greek statues - only survives as a copy later made by the Romans.

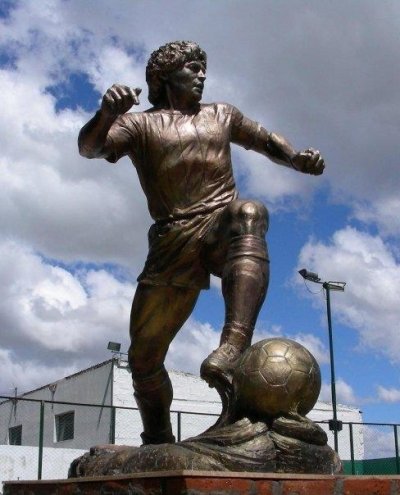

The biggest difference between modern sporting statues and those of Ancient Greece is realism.

Modern statues usually depict a named individual; we recognise their facial features, their clothes, their idiosyncracies, and personality.

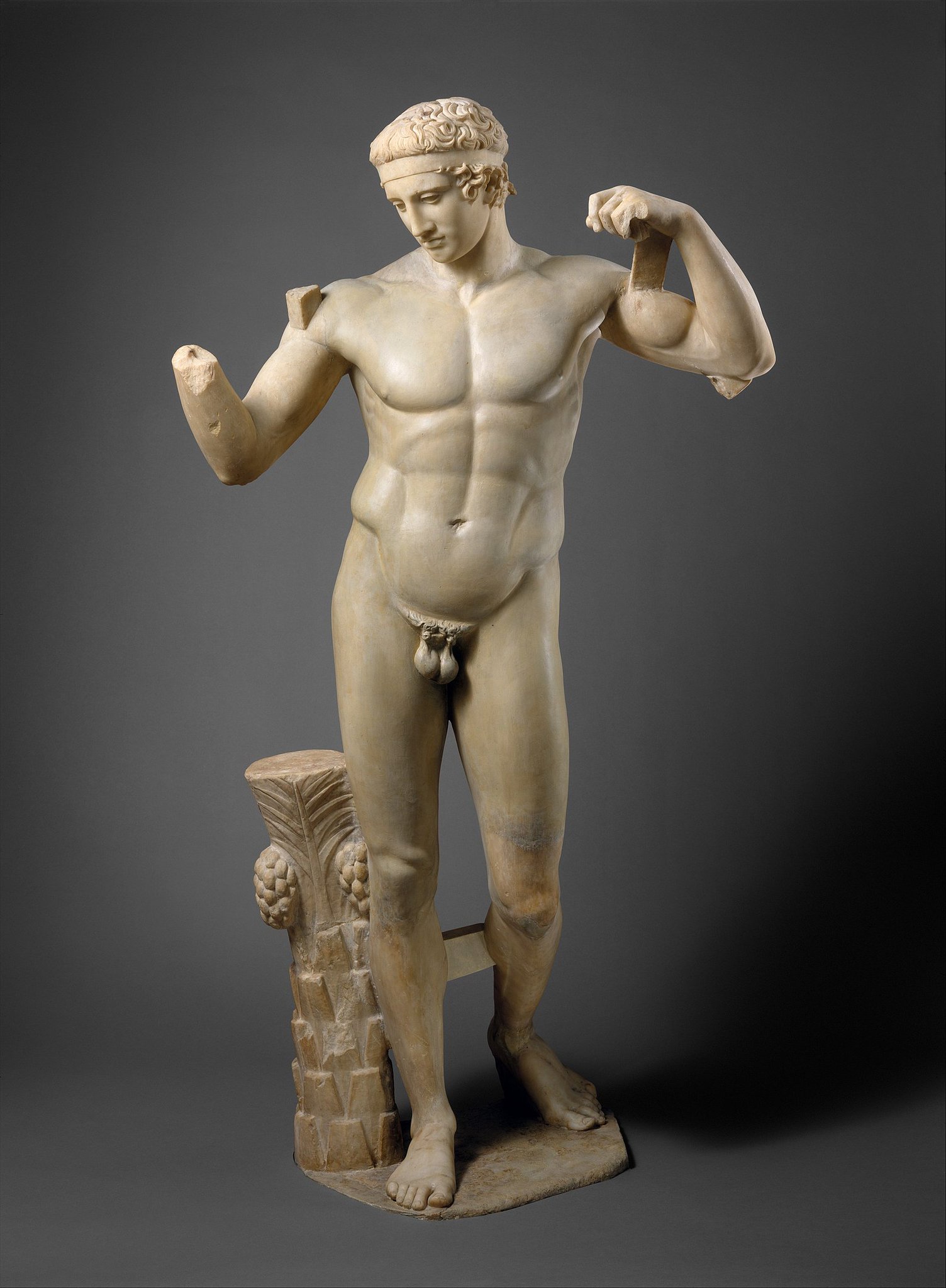

But the statues of Ancient Greek athletes weren't so much the depiction of a specified person as the representation of an ideal.

Hence why their faces so often have such similar, generic features - here we see not an individual but the Greek concept of a perfect athlete.

There were even standard forms for these athletic statues - particular poses or moments that were recreated time and time again.

Such as the Apoxyomenos, in which the athlete cleaned dust and sweat from his body with a scraping tool.

Their nudity was intended as a heroic nudity, supposed to exemplify the beauty and glory of the human form at its finest - sculptors paid close attention to the precise mathematical proportions of these figures.

Not emotionally expressive, but aesthetically striking.

Perhaps modern sport has some religious impulses; in Ancient Greece they were openly and consciously related, as sporting victors were believed to have been blessed with divine favour and their statues intentionally likened to those of the god Apollo.

Modern sporting statues are generally much more true to life, aiming to portray somebody as we might see them in a photograph.

Unlike the depersonalised, semi-abstract, idealised, pseudo-divine athletes of Greece, here what we see is unglorified, unidealised, humble, personal.

But even "realism" is a fairly broad term. It can encompass everything from a precisely lifelike recreation to one which, though recognisably that person, portrays them in a stylised or dramatic way.

Just compare these two statues of the late, great Diego Maradona.

And Ancient Greek sculpture itself became more realistic during the Hellenistic Age.

The Boxer at Rest is a good example. With his cauliflower ears, battered nose, and lacerated face he is far more realistic and expressive than the idealised athletes of 5th century Athens.

Some modern statues can seem rather lifeless in comparison with their ancient counterparts.

Perhaps, by trying to be too realistic, they end up losing any expressiveness or vitality.

Or, even worse, when realism is executed badly it can enter the uncanny valley.

And they often seem to be rather stiff. Realistic in one sense, but entirely unnaturalistic in another, like cardboard cutouts more than humans.

Ancient Greek sculptors always gave their statues "contrapposto" - a slight lean to one side - to make them more visually appealing.

Then again, plenty of Ancient Greek statues can be overly rigid, especially those from the earlier eras.

Even some of the later statues, though more natural and lifelike, are perhaps so idealised as to be distant, cold, inexpressive, and almost non-human.

While many modern statues are full of life.

Especially when they don't just show the person but convey something fundamental about their character or what they represent.

Even if you don't know who Thierry Henry is, his statue tells you everything about this ice-cold striker.

Then there's the statue of Michael Jordan, which captures not only his sporting greatness but the incredible physical and mental challenge of sport generally.

We see an athlete reaching with all he's got - splayed fingers, strained face, veins bulging - for victory.

And Bobby Moore, the legendary defender who captained England to World Cup victory in 1966, seems to be as heroic as any Greek athlete in this statue.

It's the ideal of a sporting leader as much as a portrayal of Moore himself.

Interesting about these sporting statues is that until the 1990s there weren't many; their numbers have since skyrocketed.

For a long time it was politicians, soldiers, kings, writers, public figures, and saints who got statues.

But sport, it seems, is more important than ever.

In any case, for those of you who aren't so fond of sport and find its popularity baffling, you'll have a friend in the Roman lawyer and writer Pliny the Younger.

Here's what he had to say about sport two thousand years ago...