The words we use to describe political systems originate in Ancient Greece.

Democracy comes from the Greek for people (demos) and for rule (kratos), thus meaning "rule of the people".

In which case, what was Ancient Greek democracy like?

Well, Ancient Greece wasn't one country. It was a collection of city states and regions with cultural, linguistic, and political links.

At times they were united, at others divided, they fought among themselves, and different cities had different political systems.

Some Greek cities were ruled by tyrants - individuals with absolute power - and others were oligarchies, in which a small group held power.

Democracy emerged in the city of Athens during the 6th century BC through a process of gradual reform, and flourished in the 5th century.

Only adult male Athenians could vote: no women, slaves, freed slaves, children, or foreigners.

These male citizens, perhaps 15% of the total population, were entitled to take part in the Assembly.

And it was an incredibly direct form of democracy.

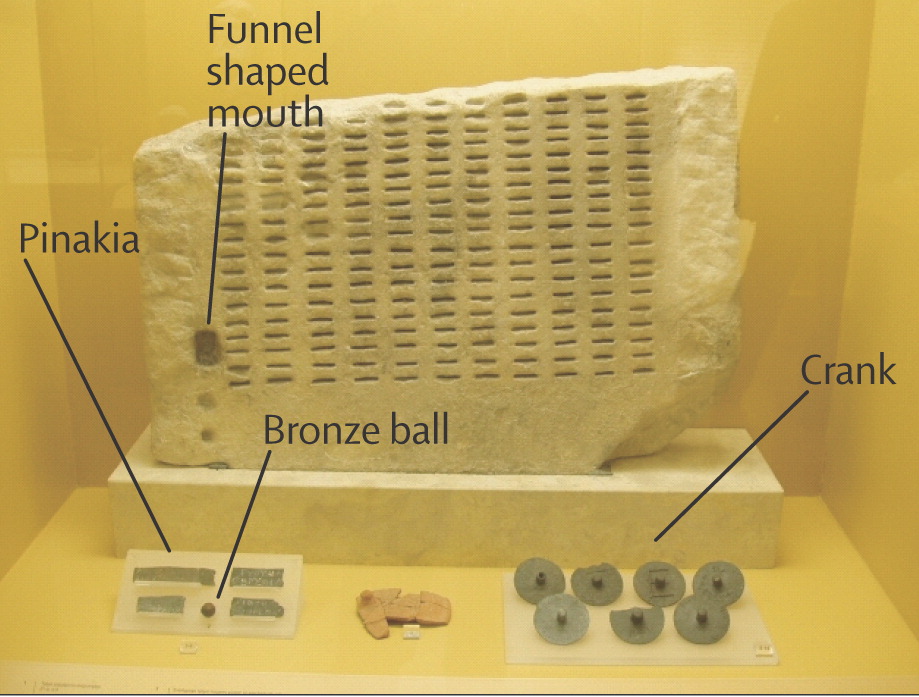

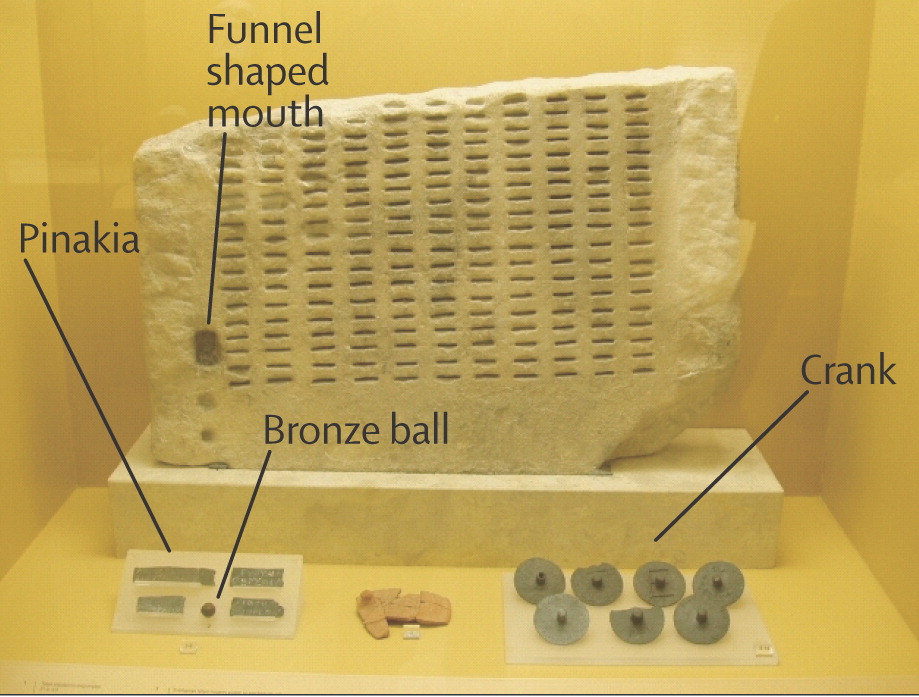

The Athenians thought random selection was the most democratic form of government - they even had randomising devices called kleroterion to avoid corruption.

The Boule, a sort of administrative city council, was selected this way, along with most public offices and the juries.

Athenian democracy was never stationary. It underwent many reforms and was overthrown on more than one occasion, only to return in an altered form.

The citizens were proud of their democracy and credited themselves with spreading it around Greece, but it was never fully stable.

And so Sparta's was the most widely admired political system in Ancient Greece. Why? Because it was stable.

The Spartan constitution was "mixed" - it involved two hereditary kings, a council of nobles elected for life, and annually elected officials too.

So the lines between different systems can be blurry.

Even "democracy" can mean many things. Do the people vote on every decision or elect representatives? Can everybody vote or only a select few? Take Athenian democracy, which was direct but didn't have universal suffrage.

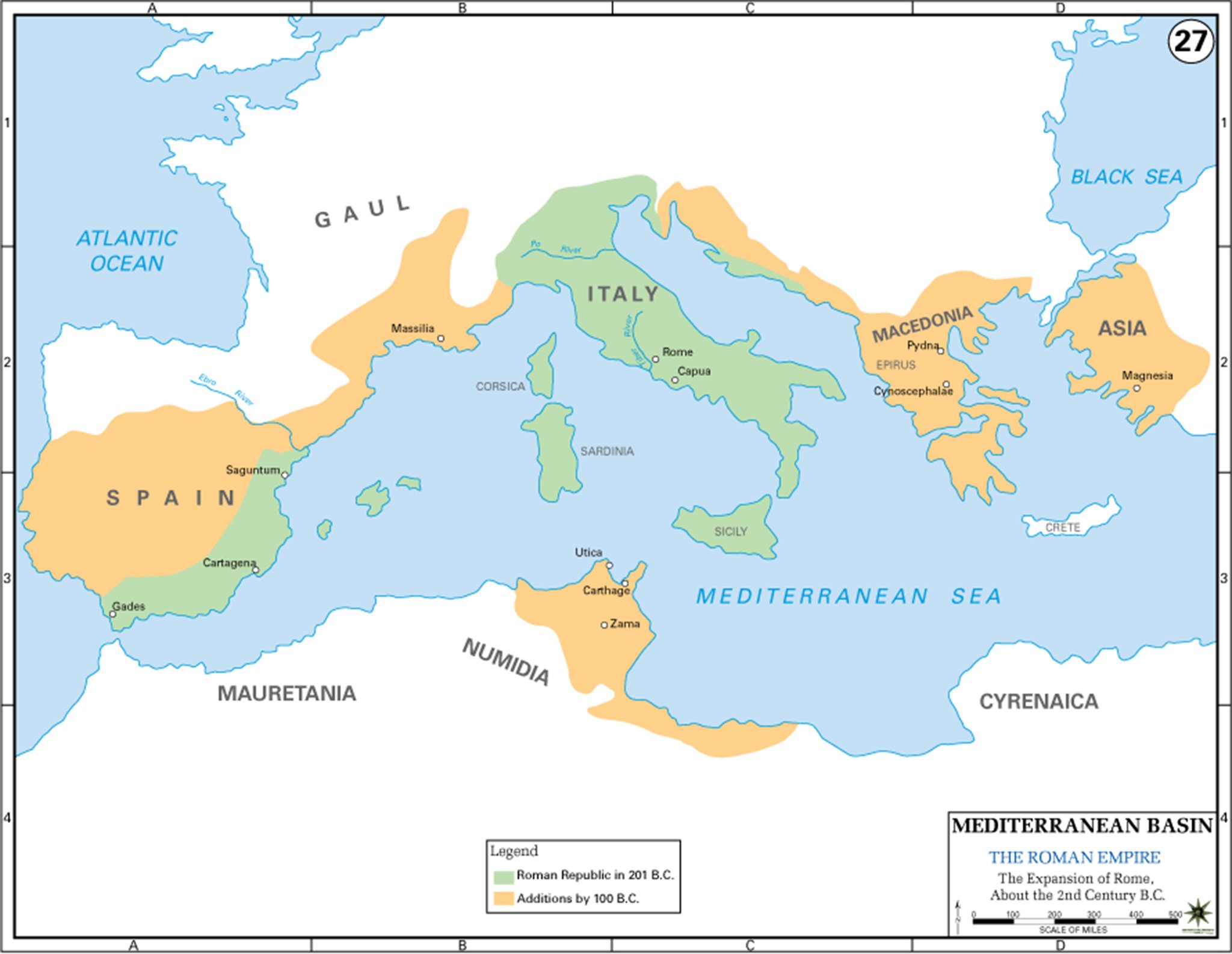

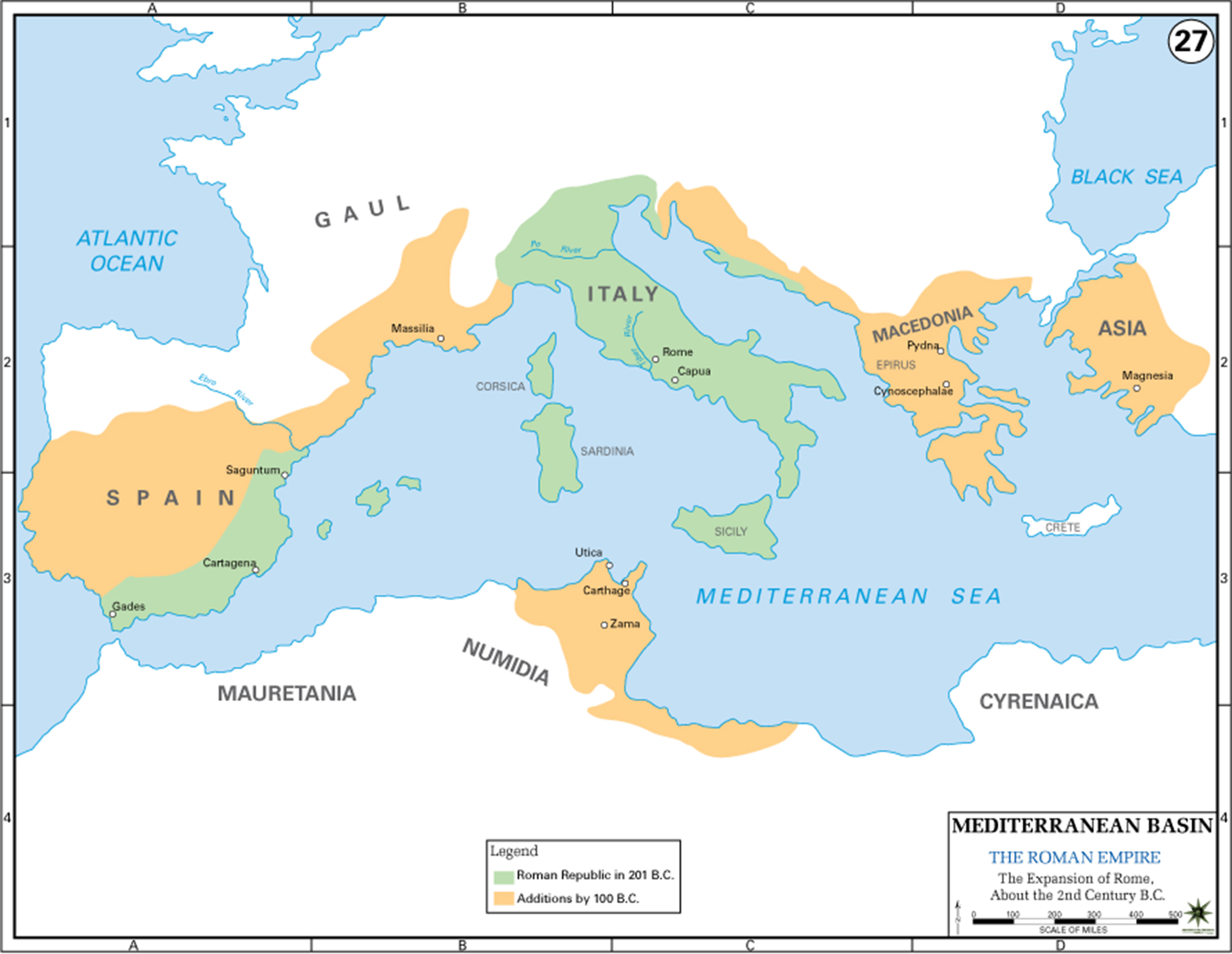

The Greek historian Polybius, who lived in the 2nd century BC, wrote a history of the Roman Republic.

Polybius wanted to understand how a single city from the Italian peninsula had managed to conquer the Mediterranean within the space of a lifetime.

Polybius was frustrated with how much instability and infighting there had been during the history of his native Greece.

He lamented how political systems rose and fell, always changing and susceptible to coups, revolutions, and civil strife.

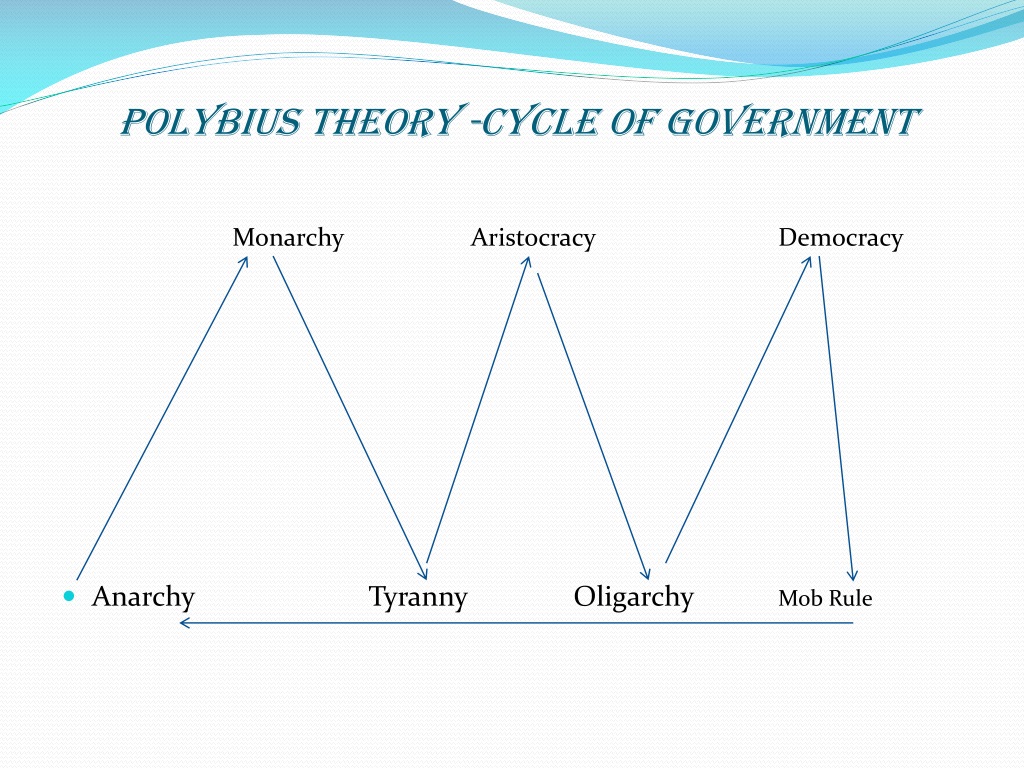

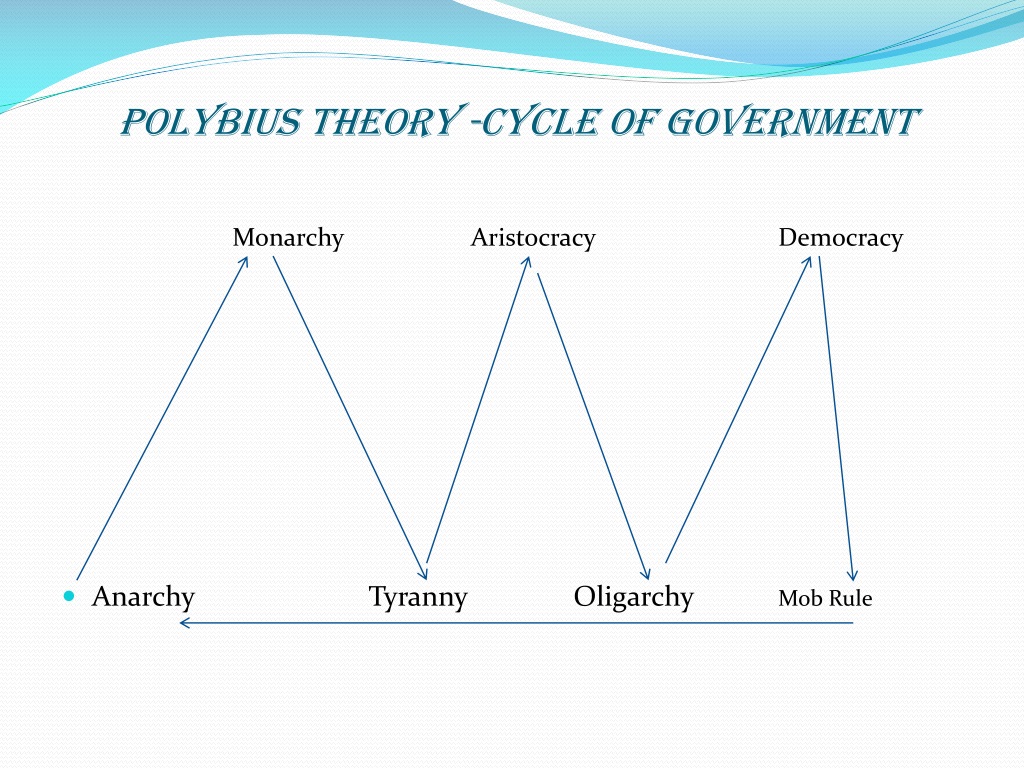

Polybius came up with a theory called "anacyclosis" - a recurring cycle of political systems - to describe the chaos of Greek city states.

There were six systems and they came in pairs: one "pure" form which naturally regressed into its "corrupt" version before being replaced.

He contrasted this with the Roman constitution which, like that of Sparta, didn't fall neatly into any of the specific Greek categories.

It balanced the king-like powers of the elected consuls against the aristocratic Senate and the democratic People's Assembly.

The French writer Montesquieu based his idea of the "separation of powers", where a political system is mixed and comprises checks and balances, on the work of Polybius.

And it was Montesquieu who directly inspired the USA's Founding Fathers and their Constitution.

But towards the end of Polybius' life the popular reformers Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus were both murdered by political mobs, and he never lived to see the Civil Wars of the 1st century BC and the fall of the Roman Republic.

What would he have written about that?

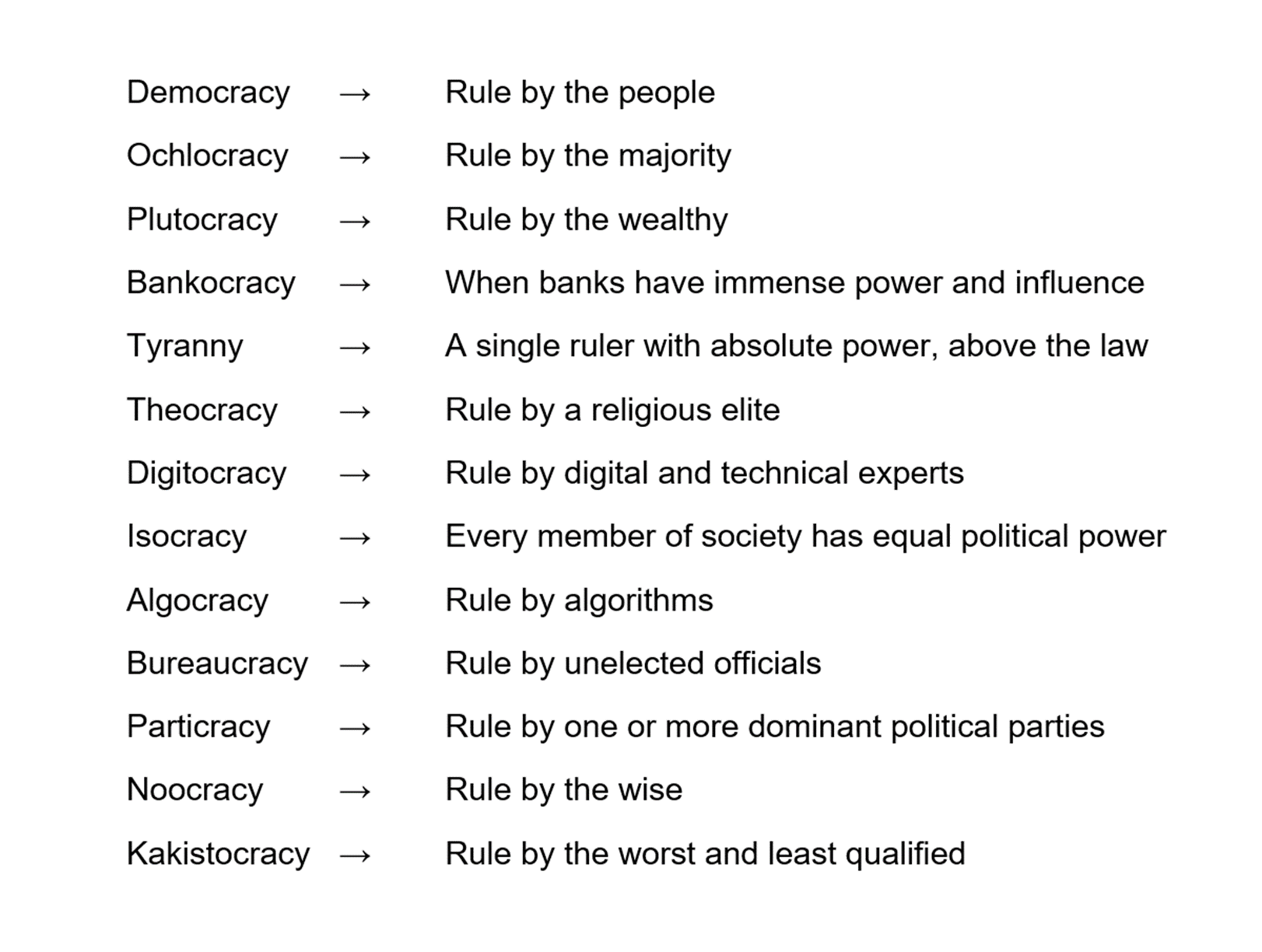

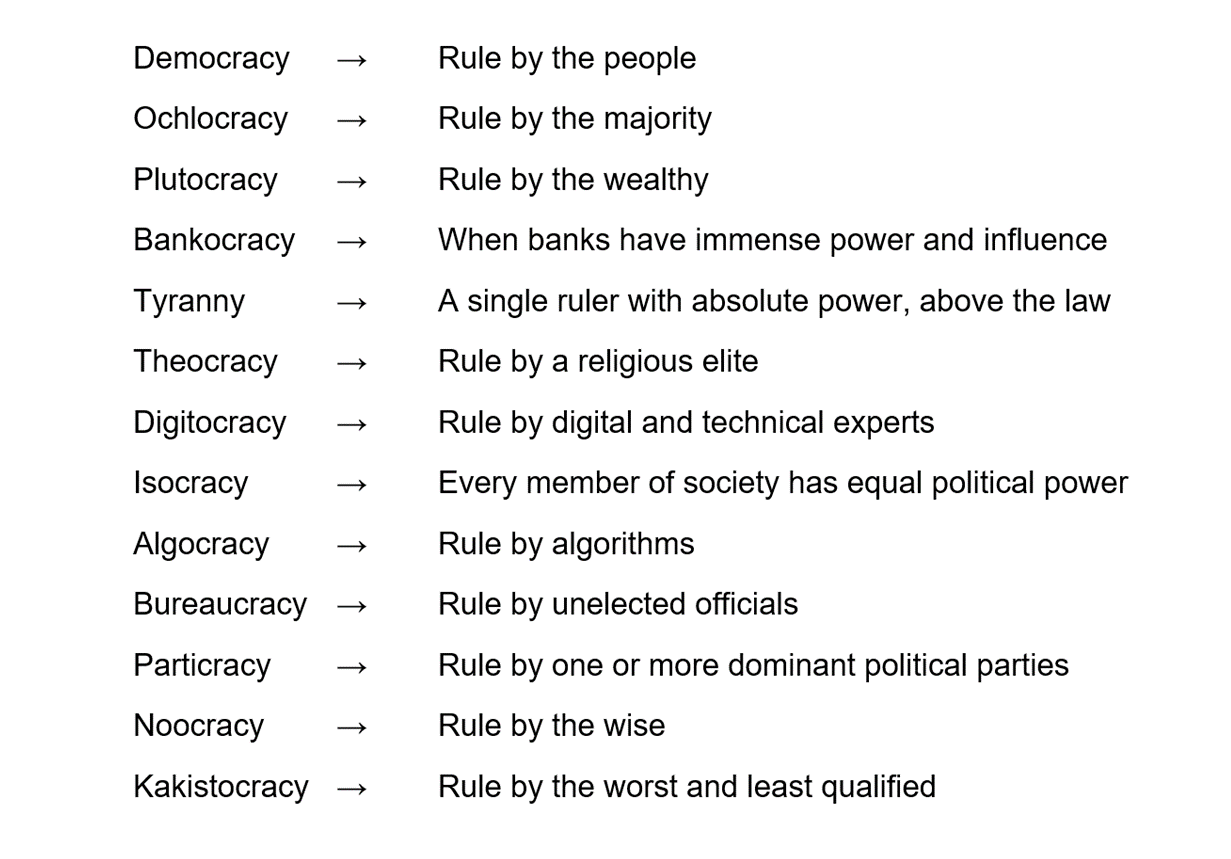

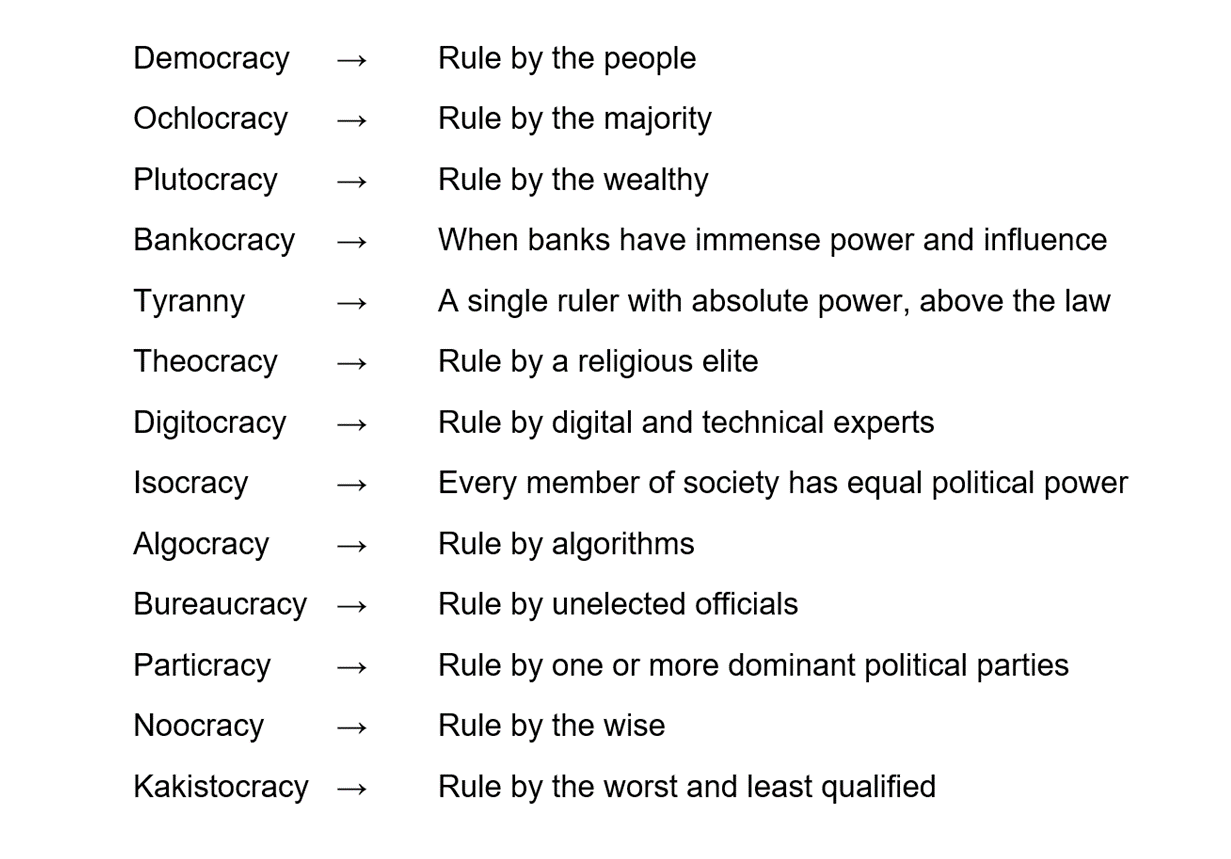

So perhaps the politics of Greece and Rome only go so far. With time more systems of government have emerged or been specified.

Of course, the Greek "ocracy" is still used to describe them - like netocracy, coined in the 1990s - but that doesn't mean they have ancient precedent.

The British constitutional monarchy - a King or Queen with symbolic power and an elected Parliament with real power - emerged from Medieval society.

It's a sort of mixed constitution, like that of Rome, but its foundations are in Norman and Anglo-Saxon law.

And there are plenty of ancient examples of other political systems, too.

The historian Josephus argued that the Jewish people had a system with no precedent in the Graeco-Roman worldview: theocracy.

Economic changes also play a role.

In the 21st century there are immensely powerful multinational banks and corporations which shape the political landscape.

There was banking and business in the Ancient World, but nothing like this; corporatocracy and bankocracy are new.

Technology too; the rise of the internet has created possibilities that simply didn't exist before, destabilising old systems in the process.

We now speak about "digitocracy", where power is held by those who own, create, or know how to use the internet and digital technology.

Much political language and theory comes from Ancient Greece or Rome and many political systems in the present day are directly based on theirs.

But context evolves. Athens had perhaps 250,000 citizens, of which 30,000 could vote; nations now have millions of people.

All of which is simply to say that political systems are rarely of one kind; they always mix different elements and naturally fluctuate over time.

So the question should really have been: which mix of these political systems do you live in?