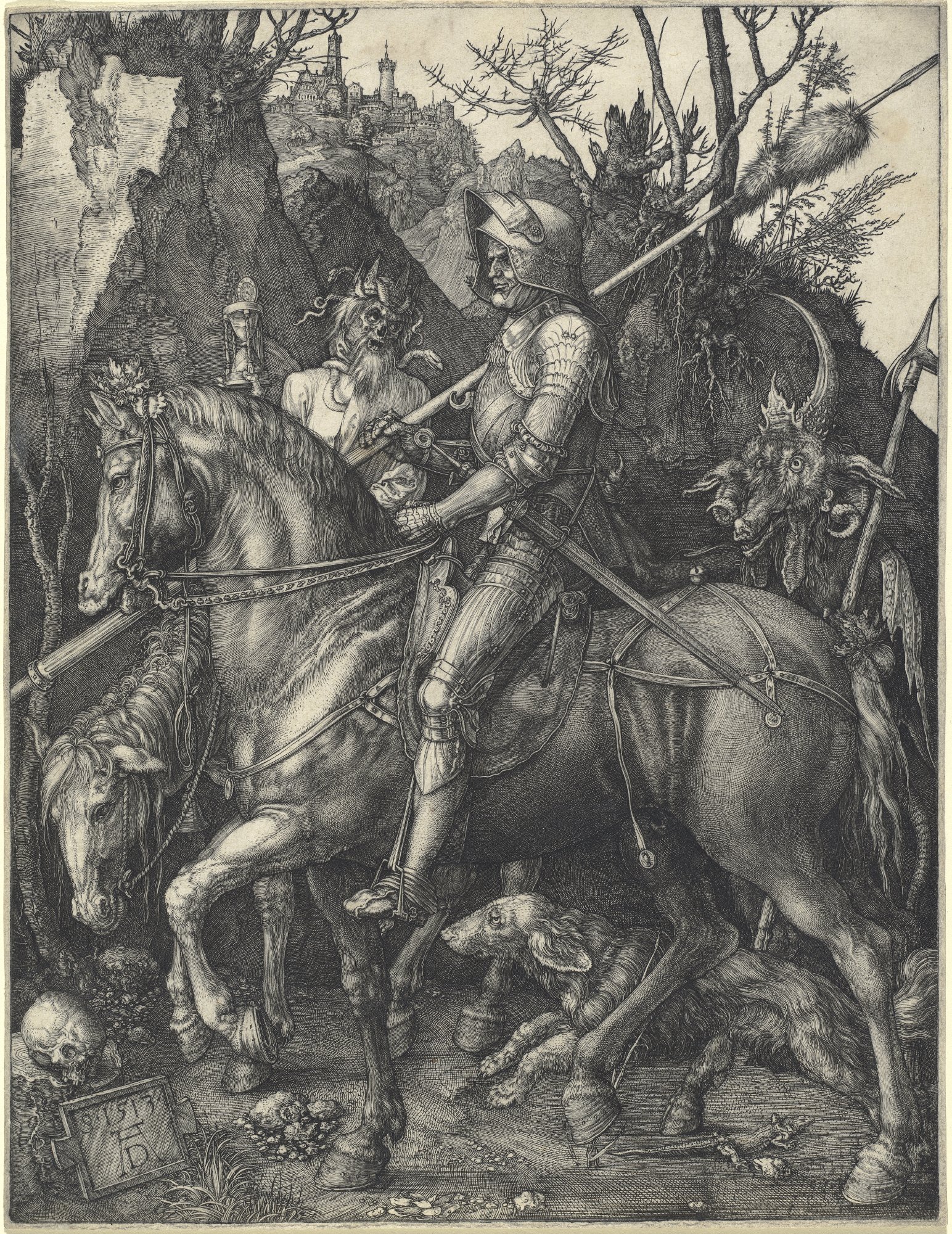

This engraving is called Knight, Death and the Devil.

It was made over 500 years ago by Albrecht Dürer, one of the most wildly talented and original artists of all time.

But it isn't actually a picture of a knight...

This engraving is called Knight, Death and the Devil.

It was made over 500 years ago by Albrecht Dürer, one of the most wildly talented and original artists of all time.

But it isn't actually a picture of a knight...

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), born in Nuremberg, was the most popular artist in Europe during his lifetime.

Why? Because he produced illustrations which spread further than any painting - which can only exist at one time in one place - ever could.

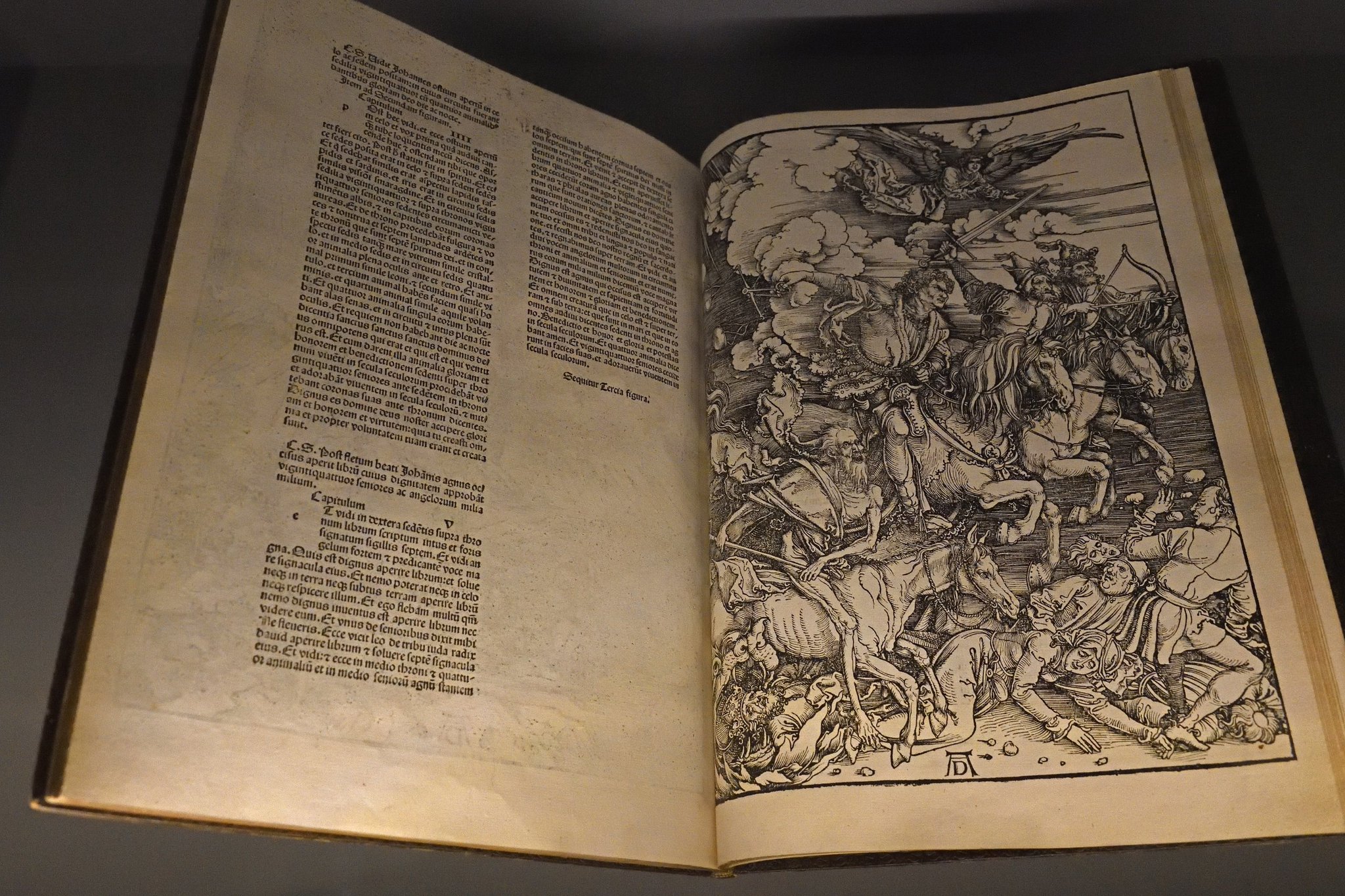

Dürer's woodcuts or copper engravings were used to create standalone prints and illustrate books.

The printing press, invented in Europe only a few decades earlier, had been a revolution of similar scale to the internet.

Information (& art) were more accessible than ever.

His illustrations of the Apocalypse, from 1498, are what brought him continental fame.

He wasn't the first successful illustrator, but Dürer brought an unheralded precision, delicacy, and energy to this artistic medium.

And his prints were sold all over Europe.

The Italian biographer Giorgio Vasari, who lived in the 16th century and wrote about Leonardo, Raphael, and Michelangelo, also discussed Dürer.

Vasari mentions the "extravagant imagination" for which he was so famous and gushes over the skill with which he matched those visons.

Dürer travelled to Italy in the 1490s and learned much from the studies of mathematical perspective and proportion that defined the art of the Italian Renaissance.

He even wrote and illustrated his own book on human proportions, worthy of any Florentine humanist.

And we can see the impact of Italian art on his own; Dürer adopted the Italian fascination with perspective, especially in the depiction of architecture, and how it creates the illusion of depth on a flat surface.

But Dürer was a great synthesiser and he also incorporated the unidealised art of Northern Europe.

His Nativity takes place in a humble German setting - as precisely envisioned as ever - and its humans are far from the beautiful, neoclassical figures of the Italian Renaissance.

He also channelled Medieval art, which paid no attention to "realism" and was filled with abundant details, physical impossibilities, and crowded scenes.

Somehow Dürer found a way to bring these three different artistic movements together and produce a cohesive, unique style.

How did he manage that?

Well, Dürer was obviously an artist with extraordinary natural gifts, one who could render seemingly anything with the utmost precision and brilliance.

Even something as simple as hands in prayer.

But this wasn't just a matter of skill - Dürer also had a remarkable personality and it was this, no less than his talent, which made Dürer such a powerful artist.

He was deeply curious about the world, whether a rhinoceros or hare, and captured it all with the same exactitude.

But that remarkable personality, which filled his work with so much energy and originality, could also verge on some truly startling egoism.

Here's a self-portrait by Dürer in a pose usually reserved for paintings of Jesus Christ - this was a man of supreme self-confidence.

He even used a monogram comprised of the letters A and D (his initials) rather than simply signing his works normally. Or not at all, as was the case with many artists.

These monograms are implanted into the world of his art, hidden on books, scrolls, signs, and bricks.

But maybe we shouldn't be surprised.

Giorgio Vasari explains that Dürer's popularity and success led others to copy him, including an Italian called Marc Antonio Bolognese, who actually passed off his own work as Dürer's.

He was an artistic superstar and he knew it.

His engravings and woodcuts are better than his paintings, but Dürer's portraits are rather interesting - and tell us more about the man himself.

Because Dürer seemed to imbue all his sitters, whoever they were, with the same intensity and angst that defined his own character.

One scholar at the time said Dürer's engravings and woodcuts are better without colour.

If we compare two versions of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse we can see why somebody might say that. Colour, somehow, detracts from the vividness and originality of his illustrations.

And, speaking of vividness, perhaps Dürer's greatest achievement was the introduction of a pyschological intensity and depth previously unknown in art, best captured by his engraving of Melancholy.

In the words of Giorgio Vasari, it "astonished the world."

Which brings us to Knight, Death and the Devil.

It was based on a book written by Erasmus, the most famous scholar of the early 1500s, whose friends included popes, kings, queens, and emperors.

The implacable, witty, moderate Erasmus is captured well in Holbein's portrait.

Erasmus was a religious reformer and a force for literacy, education, and liberalism across the continent.

He wrote in favour of divorce and the education of women; he opposed capital punishment and religious persecution.

Dürer's portrait embodies this serious, scholarly side.

In 1502 a lady asked Erasmus to convince her husband to change his errant ways, and so Erasmus wrote The Manual of Christian Knight.

The titular knight was an allegorical one whose armour and weapons were faith and knowledge, not actual blades and steel.

Dürer's illustration, a pure allegory based on Erasmus' knight of virtue, has been misappropriated and wilfully misunderstood many times, most notoriously of all by the Nazi Party, who saw it as a perfect symbol of militant German nationalism.

But that's not how it was intended.

Erasmus was a staunch pacificist who opposed all violence and war; during the bloodshed of the Reformation he argued for moderation, tolerance, and compromise.

Many people at the time believed Erasmus, with friends on both sides, was the only man who could avert catastrophe.

He also travelled widely and felt at home right across Europe, whether in his native Netherlands or in Germany, England, Italy, or Switzerland.

Erasmus was no nationalist but a true European, and somebody who believed in concord between all nations and peoples.

So perhaps Dürer wasn't the right artist to depict Erasmus' allegorical knight of virtue.

Erasmus was gentle, mild, and sceptical; Dürer was intense, zealous, and resolute.

And yet the collusion of these two minds produced one of the most captivating works of art in history...