This is the Church of Saint Sava in Belgrade, Serbia.

It was completed in 2004...

This is the Church of Saint Sava in Belgrade, Serbia.

It was completed in 2004...

Rastko Nemanjić, born in 1174, was the son of the Grand Prince of Serbia. But he turned his back on royal life and became a monk, taking the name Sava.

He later became the first Archbishop of Serbia and a key figure in the country's religious and political history.

The Church of Saint Sava was built on the site where the bones of Sava himself were burned by order of the Ottoman Grand Vizier Koca Sinan Pasha in 1595.

That was in response to a Serbian uprising against the Ottoman Empire, which had conquered and ruled Serbia since 1459.

The church was originally planned in the late 19th century, at a time when many of the Balkan nations who had gained independence from the Ottomans were seeking to establish a firm national identity.

Such as Bulgaria's Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, completed in the 1920s.

Like the Alexander Nevsky in Sofia, Belgrade's Church of Saint Sava was modelled on the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul.

It was built in the 6th century AD by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian, and has singlehandely defined Byzantine and Neo-Byzantine architecture ever since.

Remarkable about the Hagia Sophia, which was converted into a mosque after the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople (renamed Istanbul) in 1453, is its use of squinches and semidomes to create a huge central space.

This was the biggest church in the world for over a thousand years.

But the story of the Church of St Sava is long and complicated, not wholly unlike the Sagrada Família in Barcelona, which has yet to be completed despite being started over one hundred years ago.

There's a reason they call it the Sagrada Família of the Balkans.

Then again, most cathedrals and great buildings throughout history are the work of more than one generation.

Take Cologne Cathedral, whose construction was started in 1248 and halted in the late 1500s; it wasn't completed, according to the original Medieval plan, until 1880.

Serbia gained independence from the Ottomans in 1867, and in 1895 - three centuries after Saint Sava's remains were burned - a society was founded to fund the construction of a church in his honour.

In 1905 a competition was announced for potential designs...

But then came the Balkan Wars and the First World War.

In the 1920s the society held another competition and this time progress was made, albeit slowly, and in 1935 construction finally commenced.

Until the Second World War, when the German occupation put a stop to it.

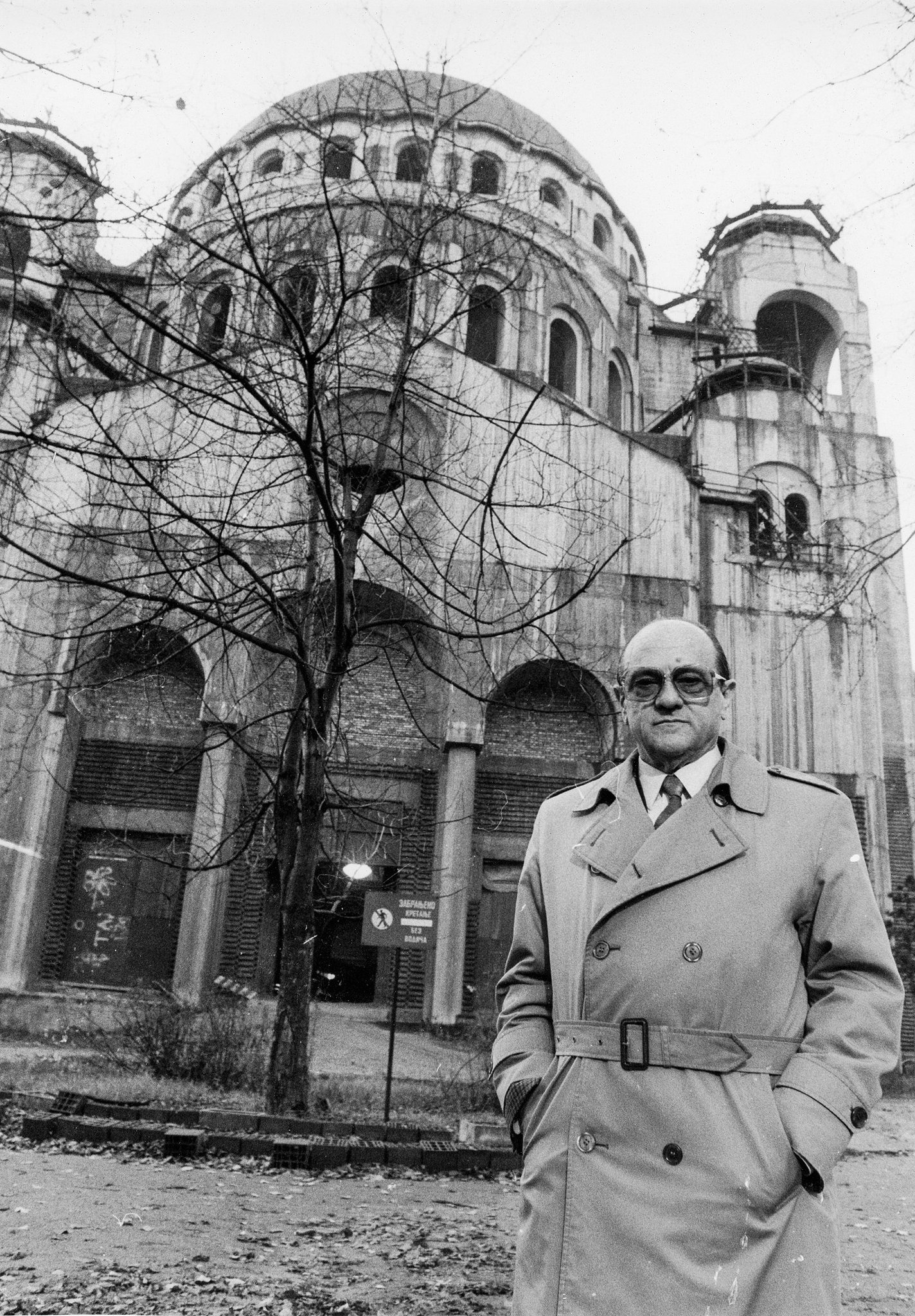

Despite efforts by the Serbian Church, the post-war Communist regime of Yugoslavia opposed organised religion and forbid the construction of Saint Sava.

Until 1985, when their stance softened and construction started according to an updated design by the architect Branko Pešić.

Interesting about Saint Sava is that it has been built with modern construction methods and materials.

Branko Pešić updated the original plan from the 1930s to make use of new technology - the structure of the church is entirely made from reinforced concrete.

A huge challenge in the construction of Saint Sava was lifting the colossal dome into place.

It weighed over 4,000 tons and took forty days in 1989 to lift it from the ground level to where it now rests, eighty metres high.

And the interior of the Church of Saint Sava has been decorated with Orthodox icons, paintings, and mosaics.

That concrete superstructure has been entirely transformed.

So what makes Saint Sava interesting is that it combines modern construction methods with traditional architectural design and craftsmanship.

Reinforced concrete was used - but sculptors and painters were also employed to create the icons and decorations of Saint Sava.

The Church of St Sava has been largely completed, its exterior faced with marble and granite, though the finishing touches to the mosaics and paintings inside are yet to be fully finished.

But Saint Sava isn't the only example of a recent building which has been designed according to traditional architectural styles and built with modern methods.

Another is the Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque in Oman, whose construction was started in 1993 and completed in 2001.

Or, still ongoing, is the People's Salvation Cathedral in Bucharest, Romania.

Its genesis, like Saint Sava, dates to the 19th century, but construction only started in 2010; it's already the tallest and largest Orthodox Church in the world.

Then there's the Rangooniha Mosque in Iran, which was built in the early 1920s for migrants from Myanmar who came to work in the oil industry there.

Though it looks old, it was built using leftover materials from the construction of the oil refineries.

Or the Great Cloth Hall of Ypres, a secular Gothic building which was built in 1304 and completely ruined during the First World War, only to be rebuilt brick for brick by 1967.

The Church of Saint Sava dominates Belgrade's skyline, a project over a century in the making which has overcome immense challenges.

And, built with both modern construction methods and traditional design, proof of what is possible with architecture in the 21st century.