The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci is not in a frame.

It's painted on the wall of a dining room for monks in Milan.

And right above it Leonardo painted the coat of arms of the man who paid him to do it...

The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci is not in a frame.

It's painted on the wall of a dining room for monks in Milan.

And right above it Leonardo painted the coat of arms of the man who paid him to do it...

The Last Supper is one of the world's most instantly recognisable images, legendary on its own merits and perhaps even more famous for how often it's been parodied or referenced in popular culture, from The Simpsons to The Da Vinci Code.

But the image we are accustomed to seeing doesn't tell the full story of Leonardo's masterpiece.

Because it isn't, like many famous paintings, on a canvas.

It's a mural, painted on the wall of a refectory in the Dominican Convent at the Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan.

Why did he paint it? Leonardo was from Tuscany and had spent his early life in Florence, after all, so why did he go to Milan?

The answer is Ludovico Sforza. He became Duke of Milan in 1494 but had essentially ruled it as Regent for his young nephew since the early 1480s.

Ludovico was both an excellent politician and a deeply learned man.

He became Regent and then Duke by a series a careful political machinations, and under his rule Milan became one of the finest and most powerful cities in all of Europe.

Ludovico was a keen patron of the arts: poets, musicians, painters, and architects from all over Italy assembled at his court.

The jewel in his crown was Leonardo, already regarded as a genius when Ludovico invited him to Milan, as recorded in the 16th century by Giorgio Vasari.

Leonardo did many things for Duke Ludovico, including building canals and fortifications.

He then asked Leonardo to decorate the Santa Maria delle Grazie, a church and Dominican convent in Milan which Ludovico was rebuilding as a mausoleum for the Sforza family.

That was in 1495, and it took Leonardo three years to finish The Last Supper.

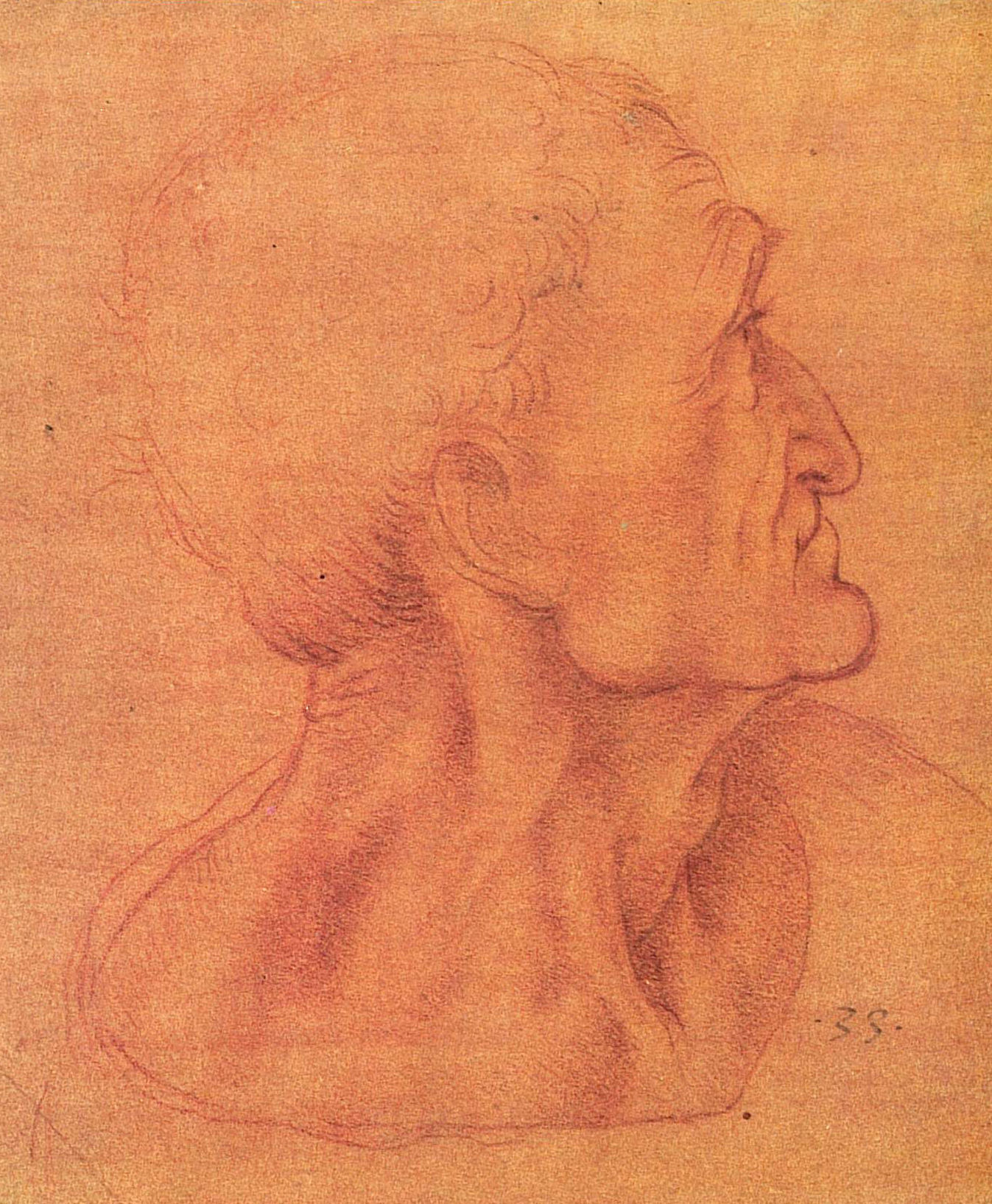

He was a slow and fastidious artist, often distracted by other things. We can tell as much from his prepatory sketches for The Last Supper, which include drawings of unrelated projects and ideas.

Leonardo depicted the precise moment during the Last Supper, as told in the Gospels, when Jesus reveals to his disciples that one of them will betray him.

Leonardo imbued each of them with a distinctive reaction based on their personalities as he understood them in the Bible.

The Prior complained about how long he was taking. Leonardo explained that it was hard to find a suitably evil model for the face of Judas, and that if the Prior wasn't careful Leonardo would use his face.

Thereafter the Prior left him alone, and Leonardo found the right model.

He never found one for Jesus. As Vasari writes, "he did not think it was possible to conceive in his imagination that beauty and heavenly grace which should be the mark of God incarnate."

So he left Christ's face unfinished, convinced no earthly representation would suffice.

Still, once completed (notwithstanding Jesus) The Last Supper was immediately hailed as a masterpiece.

The King of France even wanted to take it away from Milan, and he employed architects to figure out how they might move the entire wall back to France.

But The Last Supper has had a rough history.

Ludovico's plans never came to fruition. A separate mausoleum was built and the room Leonardo decorated became the refectory - a dining hall - for the monks at Santa Maria.

They ate breakfast right next to this masterpiece.

It quickly deteriorated because of Leonardo's experimental methods and the steam and soot and general filth of the kitchens.

The refectory was flooded several times, a new door was made which destroyed Christ's feet, and during the Napoleonic Wars it was used as a stable.

Then, during the Second World War, Milan was bombed. Much of the Santa Maria delle Grazie was destroyed but, somehow, The Last Supper survived.

It had been protected with sandbags and wooden planks, which you can see in the background of this photograph.

That The Last Supper still exists is a miracle, and even if most of Leonardo's original craftsmanship has been lost - his colours and modelling - much of his vision remains.

The deceptively simple composition, the balance, the expressions of the apostles, the overall impression.

The Last Supper is interesting because it tells us where most "great art" in history came from.

The notion of the artist as an individualistic, rebellious figure, forging their own path in the world and pursuing their own, deeply personal creative journey, is rather modern.

Leonardo, like the other great painters of the Renaissance, relied on the support of and commissions from his patrons.

Hence why he painted the Sforza coat of arms directly above The Last Supper. A reminder, if needed, that this was not an artist working in total isolation.

And that's not just true of Renaissance Italy.

Take the great Chinese painter Ma Yuan, whose landscapes are some of the most beautiful ever created. He was a court painter in service of the 13th century Emperor Ningzong.

Nor is it only true of painting. Michelangelo's David was commissioned by the city council of Florence, while Auguste Rodin's The Kiss and The Thinker both originated in The Gates of Hell, which had been commissioned by a new university in Paris.

The same goes for literature. In the Roman Empire it was Maecanas, one of Augustus' most trusted advisors, who supported writers like Virgil and Horace.

Dante couldn't have written his Divine Comedy without Cangrande della Scala, who he placed in Heaven as a mark of gratitude.

Of course, the greatest art is so great almost because it exceeds any context and becomes universal.

But that shouldn't obscure the fact that, for most of history, great art didn't simply appear. Artists needed patrons, and without them most great art probably wouldn't exist.

None of this is to say that individuals, working alone, cannot also produce great art. Of course they can, and they've been doing it for a long time.

Vincent van Gogh was a lone painter (apart from his brother's support...) who lacked not only a patron but any customers at all.

And plenty of great art has been produced by artists working in a commercial context.

So much is true of Bruegel the Elder, producing prints for the middle classes of Antwerp, or Hokusai and his wildly popular prints in early 19th century Japan, which sold by the thousands.

Still, the old model of artistic patronage was responsible for some of the greatest works of art and architecture all across the world, including The Last Supper.

Does that model still have something to offer in the 21st century?