Have you ever wondered why the world is full of glass skyscrapers?

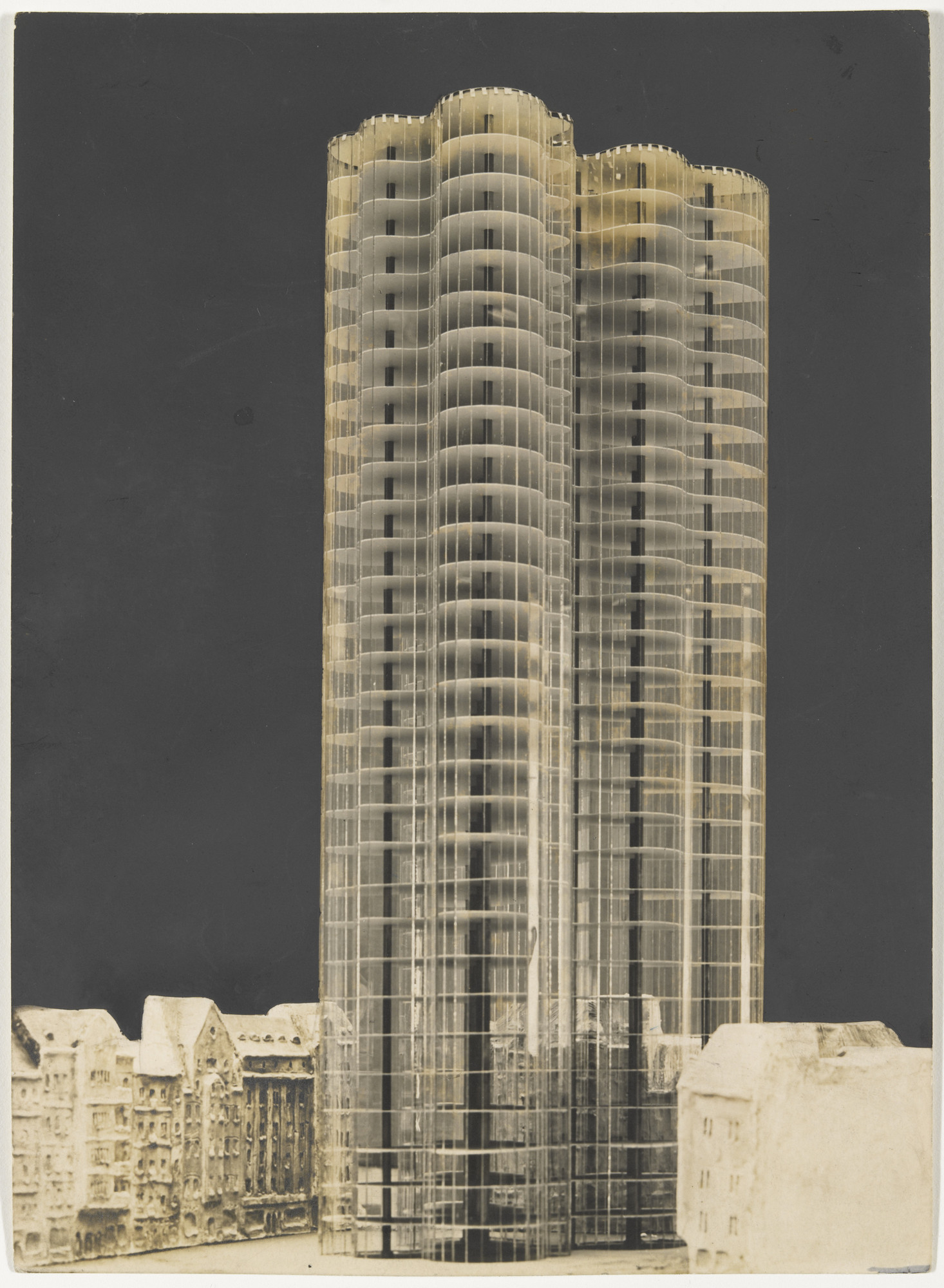

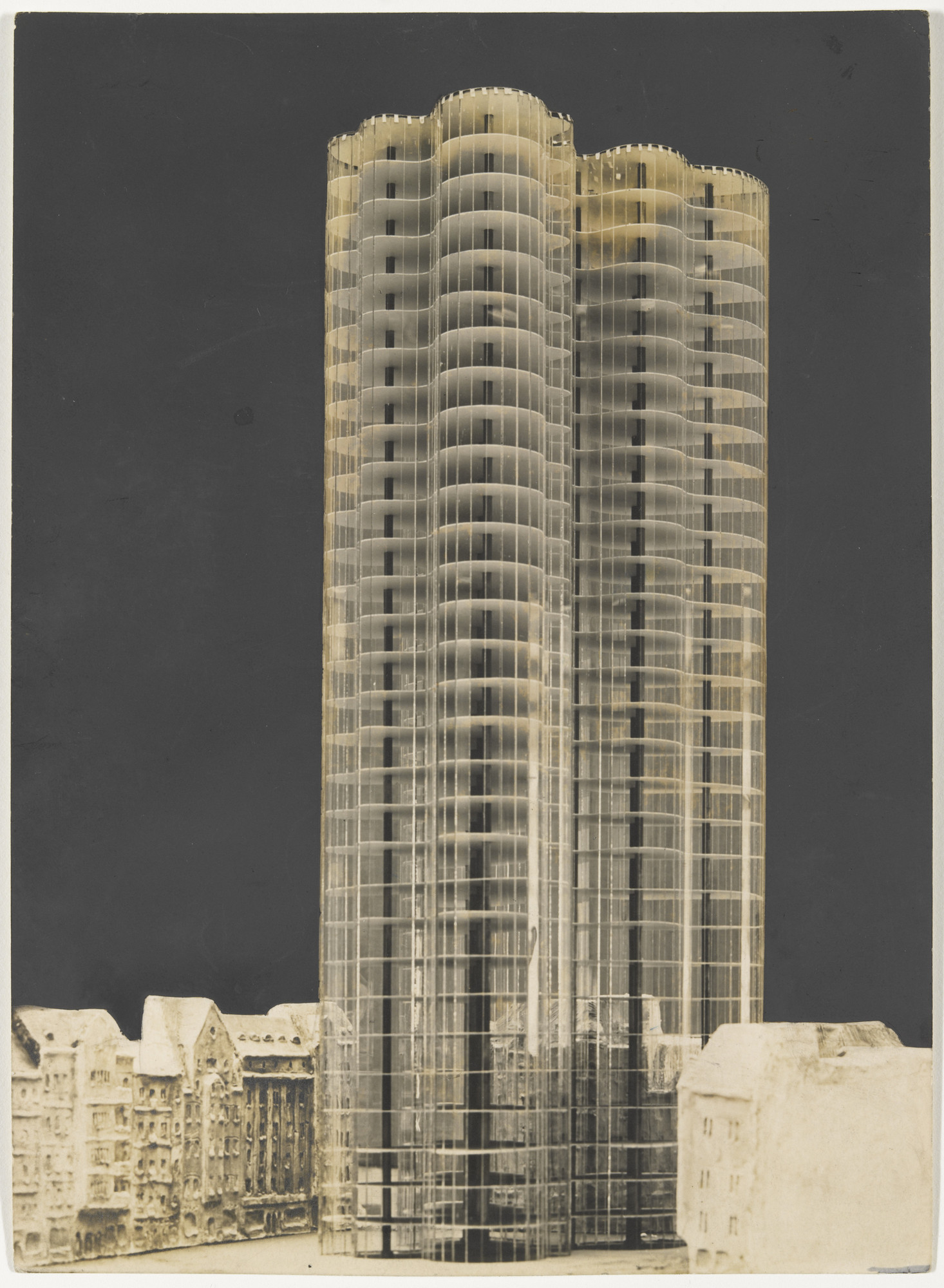

It's because of this model for a skyscraper in Berlin that was never built.

It may look ordinary, but that's the point. This model is more than 100 years old...

Have you ever wondered why the world is full of glass skyscrapers?

It's because of this model for a skyscraper in Berlin that was never built.

It may look ordinary, but that's the point. This model is more than 100 years old...

These are some photographs from the 1930s. Plenty of skyscrapers, but notice that none of them are covered with glass and none of them are purely box-shaped.

They have windows, of course, but the majority of their exteriors are made with stone or brick.

And now, in any city, if you look up at a skyscraper this is what you're most likely to see.

These buildings were designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in the late 1940s, and ever since then his ideas have shaped how the whole world looks.

But where did the story begin?

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (usually known as Mies) was born on this day, the 27th March, in Germany in 1886.

He was the son of a stonemason and grew up in Aachen, a city filled with some of Europe's finest Medieval architecture, including Charlemagne's Palatine Chapel:

It was in this environment - learning from his father's craft and surrounded by Medieval buildings - that Mies fell in love with architecture and its power to express a society's identity.

That, and the inherent beauty of materials and their textures, whether stone or glass.

Mies started training as a bricklayer but soon proved himself to be a talented designer, and in 1908 he went to Berlin to join the workshop of Peter Behrens.

Two other important Modernist architects, Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier, also worked for Behrens around the same time.

Mies learned a great deal from Behrens, who was an influential figure in the broader move away from the historical architectural styles that had dominated Europe for decades.

For context, these are some buildings that had been recently built in Berlin when Mies moved there:

In 1921 a competition was announced to design Berlin's first skyscraper. These were Mies' submissions.

He believed a steel frame could bear a structure's entire weight, thus allowing its exterior to be clad wholly in glass.

His radical proposals were rejected.

The combination of a metal frame and glass curtain wall had been around for a few decades already, as early as the 1860s in England.

But Mies realised it could be used on a far greater scale and in a far more radical way. In glass he saw the future of architecture.

After a series of private commissions Mies became Vice-President of the Deutscher Werkbund and in 1927 organised an exposition in Stuttgart which presented an affordable, modern housing estate.

Gropius, Behrens, and Le Corbusier all contributed, along with Mies himself.

So Mies had become one of the most important figures in the nascent Modernist movement in Europe.

And in 1929 he was asked to create the German Pavilion for the World's Fair in Barcelona. It became a personal testament to open space, geometric design, and the beauty of material.

Mies, influenced by the Austrian architect Adolf Loos, wanted materials to speak for themselves.

He thought steel and glass and marble, properly treated, were beautiful on their own. Additional ornamentation was not only inauthentic but a waste of time, money, and resources.

Mies and his contemporaries, like Loos, believed architecture had to change. Why?

Because technology had changed and the world with it. This was an Industrial Age and its architecture, Mies thought, should reflect that, just as the cathedral at Aachen expressed the Middle Ages.

In 1930 he became Director of the Bauhaus, an immensely influential art school founded in 1919 by Walter Gropius.

But the Bauhaus came under pressure from the new Nazi regime because of its Modernist ideas and in 1933 Mies was forced to close it down.

Like so many other members of the Bauhaus, Mies left. In 1938 he emigrated to Chicago, where the skyscraper itself had been born in the 1880s.

When Mies arrived in America its skyscrapers were Art Deco, Neoclassical, or Neo-Gothic, like Chicago's famous Tribune Tower.

That all changed after WWII, when a slump in skyscraper construction came to an end and Mies finally had the chance to put his ideas into practice on a scale no Modernist architect had previously been afforded.

In 1949 he designed these two residential towers in Chicago.

And so his vision for that Berlin skyscraper in 1921 came to fruition nearly four decades later.

The Seagram Building, completed in 1958, was the ultimate statement of his architectural philosophy. Some hailed it as genius; others compared it to a glass coffin.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s Mies left his mark all over America - and further afield.

The so-called "International Style" was born: simplified, geometric, unadorned, all glass and steel, with exposed structural elements. This style was soon replicated around the world.

How did Mies view his own work? He wanted "to create order out of the desperate confusion of our time."

And, summarising his goal: "I have tried to make an architecture for a technological society."

What had been radical in the 1920s was normal five decades later.

Mies' influence extends beyond his own work. He was head of architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology for 30 years; he taught a generation of architects.

And, as he said, "I don't know how many students we had, but you need only ten to change the cultural climate."

Well, he certainly changed the cultural climate. Many other architects also played a role in the rise of modern architecture, but it's hard to think of any more influential than Mies.

His realisation of the potential of glass, way back in the 1920s, endures over a century later.

When Ludwig Mies van der Rohe died in 1969 the New York Times called him "the leader of modern architecture". His goal was complete; Mies had created a style for the modern age.

But questions remain: Was it the right style? Was it inevitable? Is it ugly? Is it beautiful?