This is the grand Neo-Gothic staircase at St Pancras Station in London.

In 1967 it was ten days away from being demolished...

This is the grand Neo-Gothic staircase at St Pancras Station in London.

In 1967 it was ten days away from being demolished...

The 19th century was the Age of Rail, and new stations were being built all the time to accommodate the ever-growing passenger numbers.

In 1852 King's Cross Station, of Harry Potter fame, was opened.

But soon enough a new station was needed: capacity was at maximum and there were constant delays.

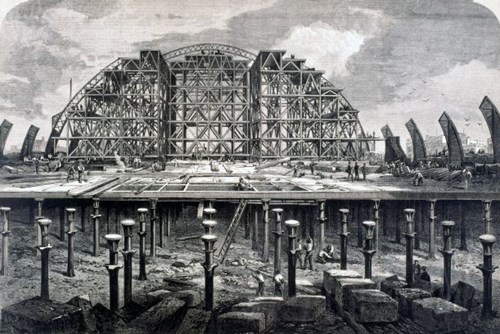

So construction began on St Pancras Rail Station in 1862, right next to King's Cross. It was a hugely ambitious project, designed by the engineer William Henry Barlow.

Three years later the station was complete. Its train shed was the largest enclosed space in the world at the time, a vast vault of iron and glass over 30 metres high, 70 metres wide, and 200 metres long.

A large undercroft was built below the platforms and concourse, largely used for the storage of beer transported into London from the North of England.

So St Pancras was complete, an engineering marvel which remains impressive to this day.

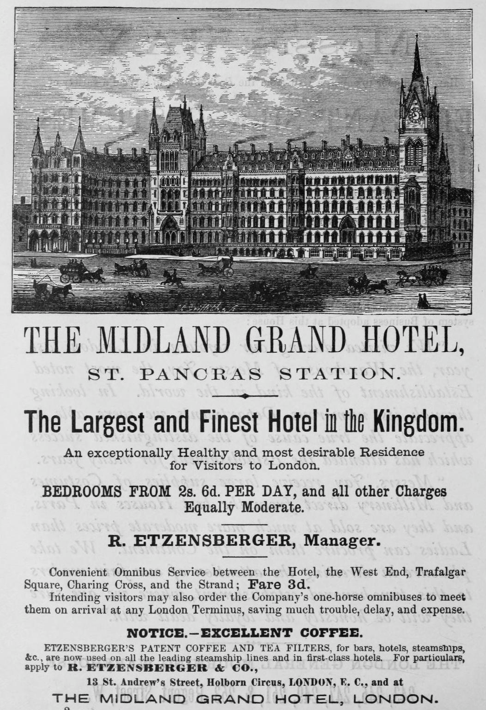

But the project wasn't finished. Midland Rail, who had built St Pancras, also wanted to construct a hotel, and they wanted it to be of the highest quality...

A competition to design the hotel was announced. The winning submission came from George Gilbert Scott, a leading Victorian architect and restorer.

He could work in the Neoclassical style, but his dream was to build a Neo-Gothic monument in London; here was his chance.

Scott, like many others, had been heavily influenced by a writer, artist, and critic called John Ruskin.

Ruskin had travelled to Venice and written a book about his investigations into its architecture, bringing back and publishing his own illustrations of buildings there.

Ruskin argued that Venetian Gothic was the finest form of Gothic architecture, epitomised by the Doge's Palace but also represented in the countless houses lining Venice's canals, distinguished by colourful facades, striped stonework, and loggias with decorative tracery.

It was this Venetian Gothic, mixed up with some other influences, that Scott used for what became the Midland Grand Hotel.

But Scott only took the Venetian Gothic as a starting point. He didn't merely imitate; he developed it into something new and distinctive.

It has - true to Gothic form - an asymmetrical design, with a large clocktower at one end, a partially curved facade, and a grand entrace at the other.

And so, 60 million bricks later, London's skyline had a new cluster of Gothic spires.

Masons carved gargoyles, capitals, statues, and friezes all over the new hotel, and the interior was filled with paintings, hand-made wallpaper, gilded ornamentation, and all manner of fine, colourful decoration.

This was the grand Gothic project Scott had always dreamed of.

So the Midland Grand Hotel was finally completed in 1873... but by 1935 it had been closed down and turned into offices for railway administration.

Midland Rail's dream of the "largest and finest hotel in the Kingdom" was over all too soon.

Thirty years later both the station and former hotel were half-derelict, with passenger numbers on the decline.

The clock had fallen down, the shed was in danger of collapsing, half its glass had been replaced with boards, and there was lasting bomb damage from WWII.

During the 1960s, like so many other 19th century buildings, both the hotel and station were scheduled for demolition.

Postwar Britain was full of badly maintained Victorian buildings, covered in soot, poorly heated, and without any clear purpose - this was one of them.

But there was a fierce campaign to save St Pancras, led by the Poet Laureate John Betjaman and the codebreaker-turned-preservationist Jane Fawcett.

And, somehow, it succeeded. Just 10 days before demolition was scheduled to begin St Pancras was Grade I Listed and saved.

Still, it would take another 30 years for the future of St Pancras to be decided.

In the 1980s it failed to meet fire safety regulations and the offices were closed down. The hotel and train shed underwent maintenance in the 1990s, but inside it was falling to pieces.

Still, the relic endured. And it was used as a filming location for everything from Batman Begins to Harry Potter and a music video for the Spice Girls.

There was something deeply atmospheric about this once-grand Gothic building in a state of abandonment.

Everything came together in the 2000s when the Eurostar, connecting London to mainland Europe, had its main terminus moved to St. Pancras.

It was fully restored, its glass replaced, and a large extension built, which you can see behind the old train shed.

The undercroft was opened up and turned into an arcade of cafes, book stores, and shops, dotted with now-famous pianos for members of the public to play.

What was on the verge of destruction was suddenly full of life, successfully modernised without the need for demolition.

And, of course, the former Midland Grand Hotel was refurbished. All of its details were carefully restored, from the wallpaper to the pink limestone and the murals to the carpets.

The Gothic ruin was alive again, as full of colour as it had once been.

Both the station and hotel at St Pancras must go down as one of the most successful restoration projects there's ever been.

For people arriving in London from Europe by train it is the first place in Britain they'll see - a grand and rather welcoming sight.

But one which very nearly didn't exist; John Betjeman famously said that St Pancras was "too beautiful and too romantic to survive".

Fitting, then, that a statue of John Betjeman now stands inside, looking up in awe at the great vault of the train shed.