One of the best ways to understand art is by looking at different paintings of the same thing over time:

One of the best ways to understand art is by looking at different paintings of the same thing over time:

The oldest known depiction of the Crucifixion of Jesus seems to be some Roman graffiti from about the year 200 AD.

It's called the Alexamenos Graffito and it's a mockery of Christianity - Jesus has the head of a donkey and the words say: "Alexamenos worships his God."

By Bonaventura Berlinghieri (1255) - Gothic

It isn't taking place anywhere in particular and there's a plain gold background with multiple scenes going on. None of it, including the people, is very lifelike.

But realism wasn't the aim here - this is pictorial storytelling.

By Andrea Mantegna (1460) - Early Renaissance

Not a pictorial story but a representation of the scene of the Crucifixion itself: there is perspective and depth and the humans are more lifelike.

But there's still lots going on and it's a heavily stylised form of realism.

By Pietro Perugino (1485) - High Renaissance

Perugino, Raphael's tutor, has moved on from the sculptural style of Mantegna to something more lifelike and harmonious.

The colours are mellower, everything is softer, and it's so much simpler; graceful rather than powerful.

By Jan Breughel the Elder (1598) - Flemish Baroque

The Italians used landscapes as a backdrop; in the Netherlands they were more important. Those brooding clouds and mountains add atmosphere as Breughel zooms out and gives a big, bustling, realistic idea of the whole scene.

By Francisco de Zurbarán (1627) - Spanish Baroque

Zurbarán removes everything except Jesus and the cross. Against a background of solid shadow it has the timeless and spaceless feel of Gothic art; but this is extremely realistic. Like a mental image with dreamlike intensity.

By Giambattista Tiepolo (1750) - Rococo

Tiepolo channels Rococo theatricality. This was the age of opera, after all, and he had even helped design theatre sets. Fluid, full of movement and loose brushwork, it's excitable, agitated, and delicate... and perhaps a little too much.

By William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1897) - Academic

French Academic Style, inspired by Raphael and the High Renaissance (emphasis on drawing, clarity, and modelling) but with an added realism.

It was this sort of thing the Impressionists rebelled against.

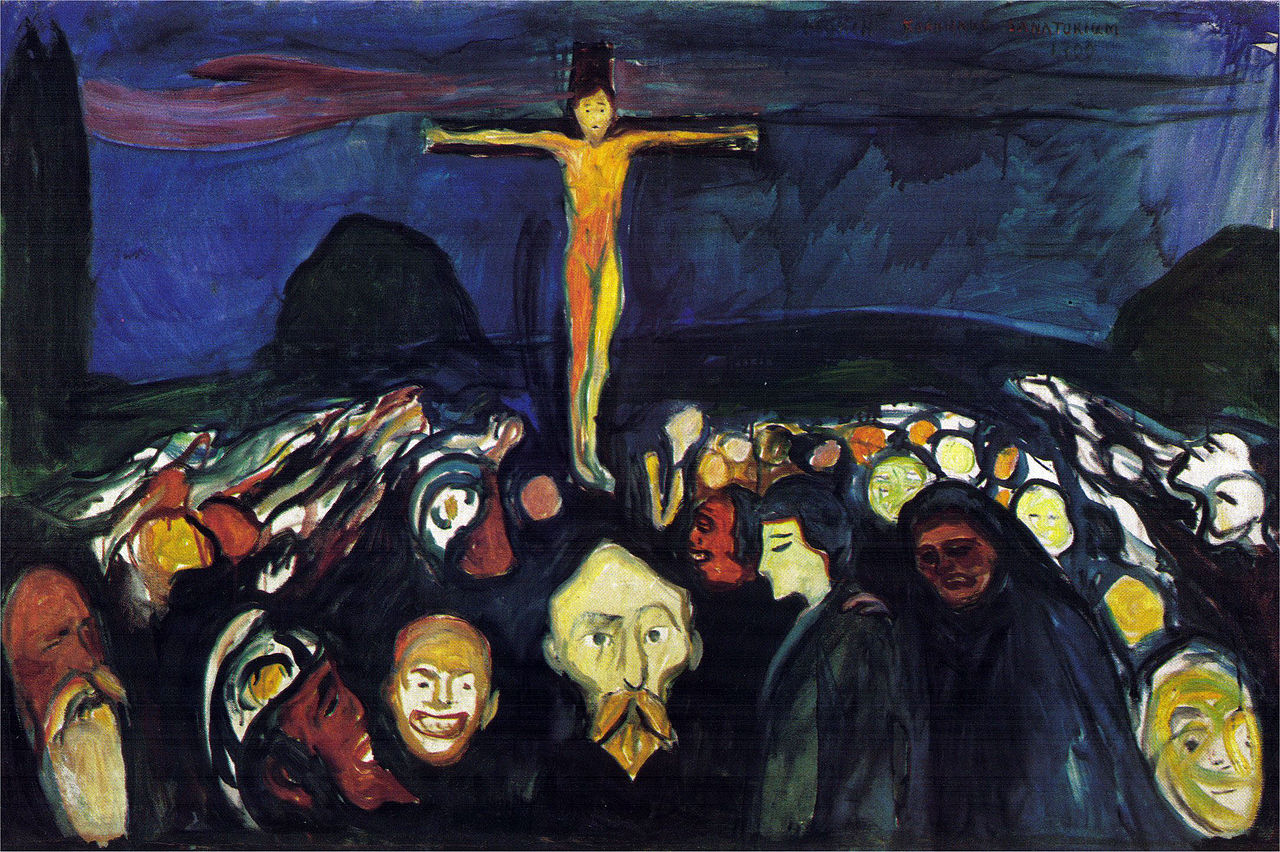

By Edvard Munch (1900) - Expressionism

Unconstrained by realism, Munch casts off modelling or depth and embraces swirling blocks of vivid colour.

New? Maybe. A return to Gothic freedom, but channelled differently: Munch was expressing psychological intensity and emotion.

By Gerardo Dottori (1927) - Futurist

Italian Futurism mixed together Cubism, Art Deco, and Abstract Art into a matrix of angular, machine-like shapes.

An embodiment of modernity and the Industrial Age, reinterpreting the old in light of technological change.

By Salvador Dalí (1954) - Surrealism

After WWII Dalí entered his "nuclear mysticism" phase, fascinated both by Catholicism and nuclear physics. Strange, dreamlike, ambiguous, and impossible - but all realistically portrayed. That's Surrealism.

And that's a brief tour through eight centuries of crucifixions - but talking about art movements is only useful if they help us understand art better.

Perhaps more interesting than whether a painting is Baroque or Symbolist is what it says about the era in which it was made...