How did people wake up before alarm clocks?!

In the 19th century there were professional "knocker uppers" who hit your window with a stick until you got out of bed.

And before that? Well, humans had an entirely different understanding of time...

How did people wake up before alarm clocks?!

In the 19th century there were professional "knocker uppers" who hit your window with a stick until you got out of bed.

And before that? Well, humans had an entirely different understanding of time...

The first question is how people even kept track of time at all; that's one of humanity's oldest problems.

First and foremost, it was through natural observation. The movement of the sun by day and of the moon and stars by night.

Astronomy is the oldest science.

It makes sense, then, that the first devices for measuring time were sundials - they were invented thousands of years ago.

After them came more complex creations, such as water clocks and hour glasses, or even something as simple as a candle marked with hour lines.

So how did people set alarms?

In both Ancient Greece and China complicated and carefully callibrated water clocks were used. Plato apparently had one which forced air through a whistle when it ran down, thus waking him up for his dawn lectures.

Then there were church bells and the call to prayer, both of which sounded at regular times throughout the day and night to mark the hours of worship and gathering.

Whether for an entire town or a monastery, this was one of the oldest communal forms of alarm clock.

Other methods were more rudimentary, such as drinking a load of water right before bed.

And then there's the sun, of course. People slept in rooms facing east so it would wake them up when it rose. Dawn also has its natural alarms: birds singing, cows lowing, cockerels crowing.

With the invention of mechanical clocks in the 14th century a new method of timekeeping was invented.

They weren't particularly accurate and were restricted to large civic or religious clock towers, but it gave towns and cities a revolutionary new technology.

Soon they were scaled down and improved; domestic clocks, even watches, had been invented by the 16th century.

Which encouraged a slew of inventive mechanical alarms; this 18th century clock has a flint-lock mechanism which lights a candle at a set time.

Which is essentially a predecessor of the modern mechanical alarm clock, first patented in the 19th century, to be replaced in the 20th century by radio and digital.

But all of this is missing the point. What's more interesting (and important) isn't so much how people woke up as why they needed to wake up at all.

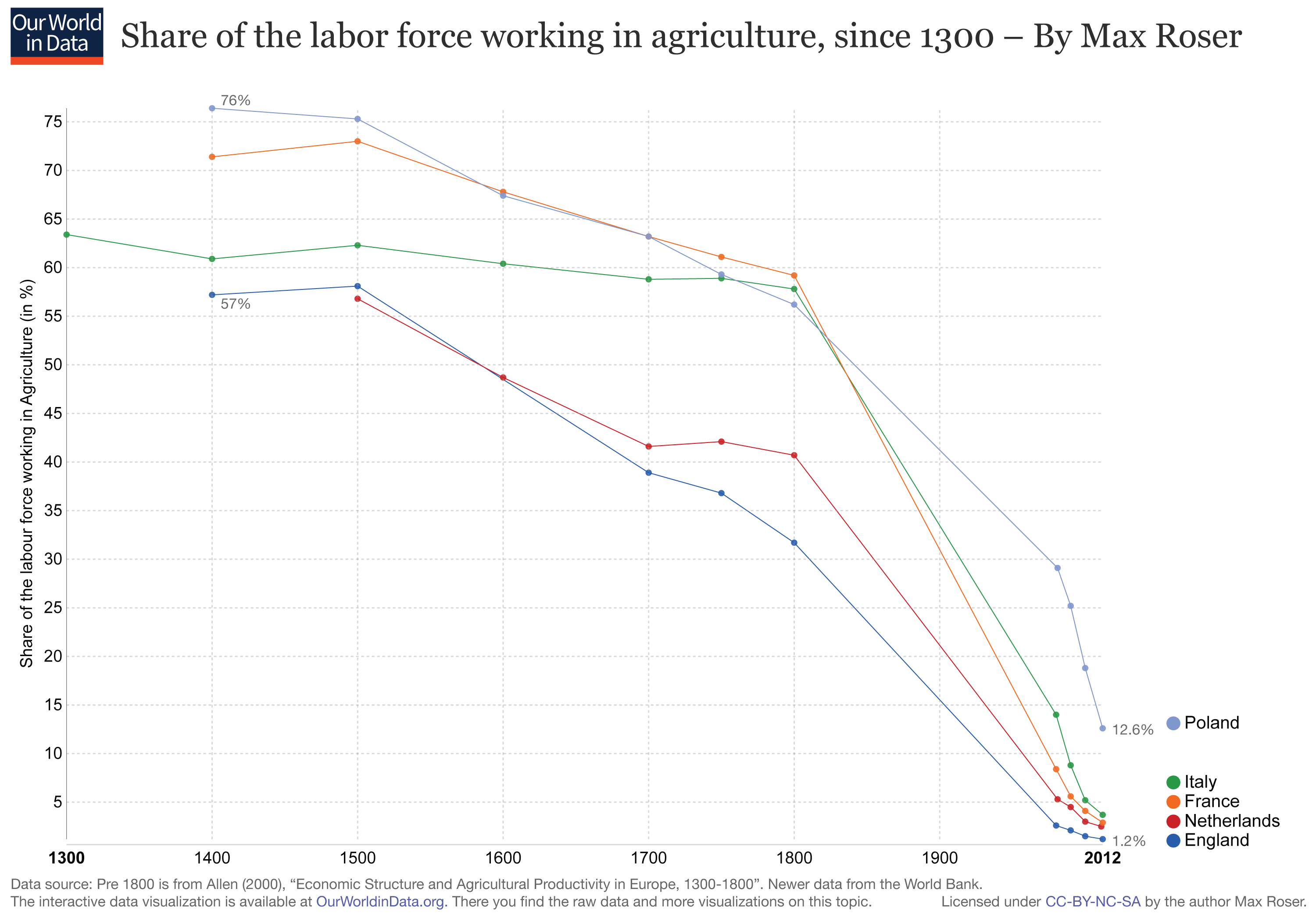

For most of history the vast majority of people worked in what we now call agriculture:

Peasants and labourers couldn't afford watches or domestic clocks, of course.

But nor did they really need to, because their "job" wasn't about how many hours you had to work but about what tasks needed to be done in any given day, week, month, or season.

Merchants, scholars, princes, monks, politicians, bureaucrats - they needed accurate methods of alarms and timekeeping.

But they represented a vanishingly small percentage of the population; the majority of people worked according to natural rather than manmade schedules.

Which brings us back to the "knocker uppers". They were needed during the Industrial Revolution because people were no longer working in nature but in factories.

It was the hours set by the manager, not the sun, which dictated when people worked and what they did.

Our relationship with time changed.

Whereas the length of hours were once variable and people divided up time based on how long it took to plough a field, roast corn, or say an Ave Maria, we now have seconds defined as 9,192,631,770 cycles of radiation of the cesium-133 atom.

The same is true for measurements and distances, which were once based on parts of the human body, common objects (like crops), or familiar estimations - a league was originally how far an army could march in an hour.

Every country used to have its own definition of an inch, nominally based on the width of the thumb - just look at that conversion chart!

We now have metres defined as the length of the path travelled by light in vacuum during a time interval of 1/299 792 458 of a second.

Such extreme standardisation - of time, distance, and everything else - became necessary in an increasingly globalised and industrial world.

Whereas every town once kept its own time, the rise of railways forced the introduction of time zones to prevent total transport chaos.

But when people worked the land and their lives were scheduled by nature, the precision of minutes and seconds wasn't necessary.

The seeds simply had to be sown before sundown; there were no Zoom meetings at 4:30pm ET to attend.

The lives of peasants were surely miserable in many ways, but they kept time by the sun and stars, worked according to the seasons and animals, with days ordered by bells and songs and time defined by how long it took to cook an egg.

And they had many more holidays than we do:

That's a broad and rosy characterisation, but such thinking prompted Romanticism.

It was inspired by this shift away from the less precise world of yore, when humans were closer to nature, to a society defined by science and industry which turned people into machines.

We still live in the world of the "knocker uppers", only now they have become phones rather than people.

And so the ubiquity of alarm clocks, something without which life now seems unimaginable, is emblematic of the evolution from a Pre-Industrial to an Industrial World.